Editor’s note: Because I failed to set up remote access to my desktop computer before traveling for Christmas, I cannot access the screenshots and videos that I would have otherwise included in order to provide the rich multimedia experience that this post warrants. I foolishly thought “Oh, this is tedious to set up, I won’t need anything from my desktop computer while I’m away.” Ridiculous. Idiotic. I always need something from my desktop computer. The editorial team at Lotus Eater regrets this grievous error and will correct it as soon as possible. Thank you.

Editor’s note the second: I have now amended the above error but will leave the note intact as a show of accountability and penance. Thank you.

2023 was a very strange year for me, both in terms of the videogames I played and my personal life. I played (at least) two AAA games about which I was not particularly fond, despite being from some of my most beloved franchises. I spent several months unable to play anything unfamiliar due to a lack of time and mental resources, which led me to do strange things like play Dark Souls 3 in some unusual ways and spend two months soaking my brain in the rich pleasure fluids of Final Fantasy XIV. I completed and defended my PhD and then subsequently started a new academic position at a new institution. I went to Japan for several weeks and (naturally) eschewed games almost entirely while there. I started eating the entire apple, including the core. I spent the sum total of several months unable to play videogames very effectively—or do much else—due to some novel health and personal issues. I also felt strangely guilty and sad that I didn’t have much of a “Game of the Year list” established by the time the Autumn rolled around and so I sprinted to complete several short games that I knew would appeal to me and rouse my Gamer Spirit somewhat.

All told, it was not an especially strong year for videogames for me, despite all of the bombastic headlines wondering whether 2023 might be the best year for gaming ever. This was mostly a reflection of the aforementioned personal issues, though is also partially indicative of my taste. I played and sort-of-disliked two well-liked AAA games this year (The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom and Final Fantasy XVI). I did not play the AAA game that I probably would have most liked (Baldur’s Gate 3) for no other reason than a lack of time and a temporarily-lowered capacity for high-investment pursuits. Other hyped AAA games, like Spiderman 2 and Resident Evil 4 Remake, appealed to me, but not enough to actually demand my money and time at the point of their release. Smaller releases, like Dredge and Cocoon, certainly caught my attention, but again failed to make it out of wishlist status. This is all to say that I did not really adequately sample the Delights of Gaming’s Newest Best Year Ever, but the Delights were also not always that appetizing to me.1 This is especially so in comparison to 20222 and 2021,3 which were incredibly strong videogame years for me (and were much less tumultuous personally).4

That said, December is the time of the year that we have all agreed to look back and take stock on our media consumption, eagerly declaring our favourite games, movies, cereals, and liturgies of the year. That may sound ironical but I genuinely love Game of the Year lists and deliberations. They are completely meaningless and arbitrary, of course—that’s what makes them fun. I love listening to people good-naturedly argue with one another about this foolish topic and commit far too much effort and emotional investment to it each year. And so, that I might become an active participant in this Tournament for Fools and Idiots, I present the 2023 Lotus Eater Games of the Year, complete with a brief write-up for every game honoured with the distinction, along with a contemplation of some of the other gaming experiences I had this year. As with my previous Game of the Year write-ups (presented and maintained elsewhere), I deem any game eligible so long as I played it for (effectively) the first time this year. This means that older games that are new to me, like Touhou Luna Nights or Warm Snow, are eligible, whereas perennial Lotus Eater favourites, like Slay the Spire and Dark Souls 3, are not. This is largely because I do not have the time, money, or disposition to follow the whims of the market and release dates, and I instead play the games that Call to Me Most at any given moment, or at least the ones that I think might most effectively Temporarily Subdue My Ego. Without further ado, I present to you this unordered list of my favourite games of 2023.

ARMORED CORE VI: FIRES OF RUBICON

As intimated in this post and others, I am what you might call a fan of the FromSoft franchise of videogames. I have collectively invested somewhere in the neighborhood of 500 hours into these games, count several of them among my favourite games of all time, and revisit them like a comfort food or an old familiar friend.5 I used to be a hater of the FromSoft franchise of videogames (Lotus Eater post coming 2024), but thanks to the confluence of encouraging friends, a global pandemic, and a rhythm-game-disguised-as-shinobi-swordplay-game, I am now desperately attached to them. So, naturally I was excited when they announced a new entry in the Armored Core franchise, a series with which I had no prior experience (but about which I was certainly curious).

Armored Core VI: Fires of Rubicon is a PS2 game sent forward in time to the present. To use the parlance of the day, it is a “videogame-ass videogame.” It sends the player on short, tight, well-designed missions in which they use a giant robot to kill other robots of varying sizes.6 The game encourages the player to experiment and iterate on their mech by allowing them to purchase and sell mech parts for the same price, thereby mitigating the potential punishment of choosing incorrectly. This allows even a casual player to sample the massive variety of viable playstyles in ACVI, which has traditionally been a weakness of FromSoft’s games. The Dark Souls games, for example, often prevent any experimentation entirely, by disallowing any stat re-speccing or (of nearly-equal importance) weapon upgrade reallocation. ACVI operates under a completely different philosophy, instead requiring players to repeatedly re-design their mechs for the situation or boss that currently threatens them.

This philosophy dovetails well with ACVI’s gameplay loop: its missions are tight, fun, compelling, and offer a great variety and the perfect length for experimentation and replaying. And, most crucially, the movement and combat in these missions is utterly pristine. What the game lacks in overworld design (instead favouring smaller-scale discrete levels), it absolutely makes up for in fundamental playability. Very few games look and feel as good as ACVI. The mechs are responsive, weighty, and “real-feeling”; it is the perfect blend between the hefty “realistic” movement of a mechanical behemoth and the celluloid fun of maneuvering an imaginary object in virtual space. Even compared to FromSoft’s other “souls” games—which are rightfully renowned for their combat—ACVI is an absolute joy just to play.7

I have no grand criticisms of Armored Core VI: Fires of Rubicon. My main critique might be that—unlike some other FromSoft games—ACVI is not life-rendingly-excellent. But honestly, that’s sort of welcome at this point. It’s so exhausting to have my understanding of videogames challenged and updated. I loved having a simple 25 hour experience that was solid and frictionless and enjoyable. There were aspects of the game that could have been better—namely, its bosses, which were mostly fine but featured only a couple of truly memorable fights—but I can’t really bring myself to level a full-throated complaint about these weaker aspects. My biggest complaint is perhaps that the mech building and customization is extremely intimidating and that this never really goes away, even by the end of the game. It can be so difficult to tell whether Part A is better than Part B, even after a dozen hours of shooting and gliding and slashing. Fans of the game will tell you that “Every part is good! Just play what you like!”, but that doesn’t really make the process any more transparent or any less intimidating. There are literally dozens of parts, all with names like “HML-G2/P19MLT-04”, and those never became any more comprehensible to me. I did still manage to find several builds that I enjoyed though and I’m sure that if I had dedicated more time to it, I could have become a master engineer.

These small critiques notwithstanding, Armored Core VI: Fires of Rubicon was an absolute pleasure to play and was one of my favourite experiences of 2023. It was a wonderfully-novel presentation of decidedly-retro gameplay.8 In a year filled with disappointing AAA experiences (for me personally), ACVI was encouragingly refreshing.

THE CASE OF THE GOLDEN IDOL

I played Return of the Obra Dinn for the first time in 2019. As far as I was concerned, it represented the invention of a new genre,9 and I now hunger for this particular type of deduction-heavy immersive puzzle game at least once per year. The true Obra Dinn-like of 2023 was probably Chants of Sennaar, but I’m bad at playing new games when they come out, and so instead I played 2022’s best Obra Dinn-like: The Case of the Golden Idol. A deliciously-ugly game with hypnotic music and immaculate vibes, The Case of the Golden Idol has players solve a series of increasingly-complex and interrelated murder(ish) cases using only simple dioramas and the scalpel of deduction. Its writing was charming, its difficulty curve was elegant, and the esoteric surprises revealed in the unfolding narrative were a source of constant delight for me. I found the game totally engrossing and deeply satisfying and so naturally I started and finished it within the span of about 26 hours,10 which is about as deep a compliment I can pay it as a Notoriously-Slow Game Player. I found myself completely addled by Golden Idol’s moment-to-moment gameplay, its cases, and its broader mysteries, and I look forward to playing both its DLC and its recently-announced sequel.

Here is another compliment that I can pay The Case of the Golden Idol: I beat the entire game without using any external aids or its in-game hint system. This is not especially unusual for me—someone whose arbitrary perseverence (stubbornness?) borders on the pathological and far exceeds the threshold of utility—but it does help introduce something unique and intriguing about the game. I was curious at one point about how the in-game hint system worked and so I clicked on the Hint button. The game then takes great pains to warn you: Maybe you don’t need a hint. You can do this. Put in the effort and you can solve this. The potential of the human mind is unlimited. Or something like that. The game also warns you that if you do decide to take a hint, you will have to complete a “task”, meant to make players even more hesitant to ever use a hint. This was enough to deter me from even experimenting with it and so I still do not know how its hints work or what task it first requires of players. This is, as far as I’m concerned, an excellent bit of game/UX design. Players are rhetorically and mechanically dissuaded from relying too heavily on hints, but are given the opportunity to use them if they are desperate. And, hopefully, most players will be so encouraged by the game’s anti-hint stance that they end up completing the game without using them at all.11

The Case of the Golden Idol is one of those rare games that I would recommend to nearly everyone, even non-videogame players. It is ruthlessly lean, relying almost exclusively on cognitive mechanics that are available to most humans. Its strange little cases will delight nearly anyone, its secret societies and arcane metaphysics will ensnare even the only-lightly-esoterically-minded, and its perfect clockwork machinery will soothe those with a craving for Order and Perfection.

CITIZEN SLEEPER

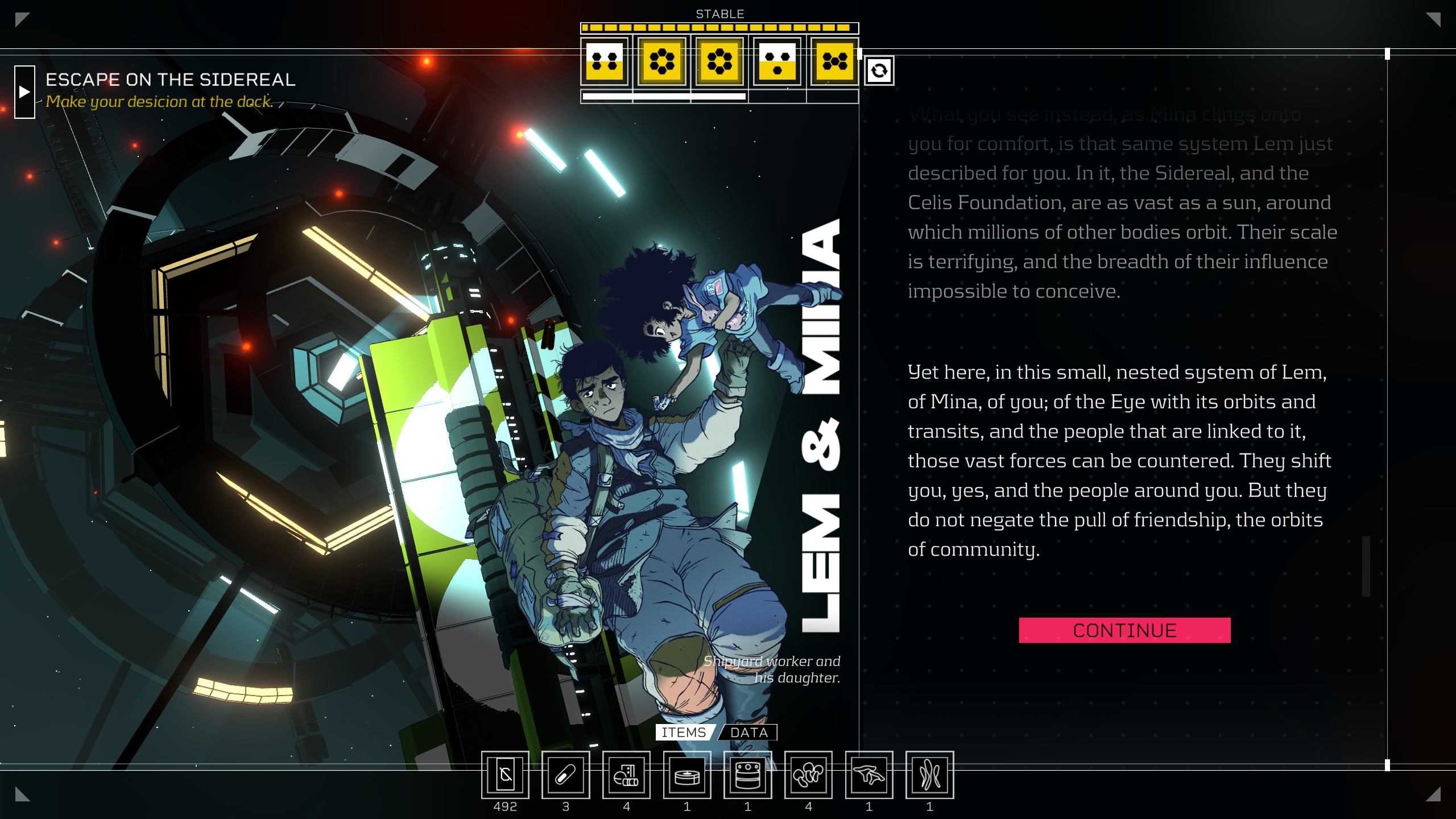

Staring down the barrel of an Autumn in which I had not yet played five games worthy of a “Game of the Year” list, I once again found myself playing one of 2022’s beloved indie sleeper hits. Citizen Sleeper is part cyberpunk visual novel, part sci-fi role-playing game, and part resource management board game. Players take on the role of a sleeper, an android-clone of a human created to perform physical labour and designed to perish without a drug produced by its manufacturer. This puts players in a tenuous position, as the game opens with your escape from the labour camp onto a space station with decidedly-little of the aforementioned drug. From there the game begins to weave an impressive illusion that remains unbroken for the majority of its runtime: the perception that the player is both radically free and under extreme threat. In truth, the player’s options are fairly circumscribed and she is unlikely to be in any true danger. But the combination of these two perceptions makes for an especially potent and immersive gameplaying experience that had me obsessively optimizing my resources and time, while also pushing forward in my exploration of the space station and its inhabitants.

For the duration of that illusion, I found myself both narratively and mechanically obsessed with Citizen Sleeper. The game expertly weaves the narrative and mechanics together, allowing the dire and destitute tone of the world to inform the perilous and impoverished gameplay, and vice versa. In this way, Citizen Sleeper is both a virtual emulation of a tabletop role-playing game and an example of (what I consider to be) the gold standard of videogame storytelling: using mechanics to tell a story that could not be presented effectively in any other medium.12 Beyond that, the game also features incredible writing, excellent music, and wonderful vibes. The game is mostly perfectly-paced and consistently offers intriguing options for moving the story forward.

The game is not flawless, of course. The final third of the game can drag a bit if the player has been too successful in resource management; as they have become Unto a God on the space station, the only thing limiting progression is the passing of days. This particular frustration is exacerbated by what I would call a fairly poor UI experience, which is all the more salient in a game that has so few things anyone would describe as “poor.” The map and menus are generally janky and unpleasant to use: for example, getting from the top of the map to the bottom requires a shocking amount of hammering on one’s scroll wheel. If this weren’t enough, the player also has to make several (ostensibly-unnecessary) menu prompt clicks along the way. This whole process tends to interrupt flow and immersion and also gets especially enervating at the end of the game when one is mostly just burning time to run down clocks. These flaws are relatively minor though and ultimately have little impact on what is broadly an excellent experience. Moreover, they are the exact sort of minor flaws that can be fixed in the upcoming Citizen Sleeper 2: Starward Vector.

THE TALOS PRINCIPLE

The Talos Principle is perhaps the most egregious entry on this list: it was released in 2014 and has been in my Steam library since 2018 and so it probably should not be eligible for a 2023 GOTY list. That said, its sequel did come out in 2023, so maybe that helps to qualify it. The game’s age is also not irrelevant to my experience with it. Up until basically this moment, I had thought of The Talos Principle as being a “Witness-like.” It is only now that I am really realizing that The Talos Principle precedes The Witness by over a year. It is a game that was definitively not inspired by The Witness,13 which, to me, makes it all the more impressive. The Talos Principle has players take on the role of a robot in a world that is seemingly inhabited only by himself and the disembodied voice of God. Over the course of the game, the player unravels the mysteries of the world and their own existence, primarily through monologues from God or through reading documents on a terminal.

That description belies the true value of The Talos Principle, however: puzzles. This thing’s got so many puzzles. It has so many different types of puzzles. It’s got logic puzzles, it’s got physics puzzles, it’s got speed and platforming puzzles. It’s got puzzles where you have to follow the rules and puzzles where you’re rewarded for exploiting the game. It’s got puzzles where you have to do a modern (less-frustrating) version of “pixel hunting” and it’s got puzzles where the solution is hidden within a bit of graffiti poetry. Don’t like a certain type of puzzle? Good news, just about every puzzle is optional (sort of) and there are about a dozen other types of puzzle and about a hundred other puzzles. These puzzles are remarkably consistent in quality, difficulty, and creativity. They reward lateral thinking and unusual approaches, often having multiple solutions (and even multiple types of solutions) and encouraging players to “break” the game in some small way in order to solve a grander “meta-puzzle.” Playing The Talos Principle felt like a vice or drug or other shameful indulgence because of how intensely and consistently it brought me Raw Pleasure. For a certain type of person, there are few things so rewarding as solving a well-tuned puzzle, and for that person, The Talos Principle might as well be pure high-quality heroin. And, just like with heroin, The Talos Principle isn’t even bad for you—it’s basically vegetables the videogame. It doesn’t use cheap tricks to generate quick highs and an ill-earned sense of reward (in the way that, say, a predatory free-to-play game does14). It doesn’t dilute its experience with filler tasks or low-quality puzzles or time-consuming fetch quests. It is just straight, clean, Croatian dope that you can mainline until your eyes roll back in your head.

I also generally enjoyed the tone, style, and writing of The Talos Principle, but it was largely just set-dressing for me. I did not find its philosphizing especially insightful or novel, though I did not find it trite or cloying either. These elements of the game were just a(n admittedly-lovely) skin over an excellent and versatile puzzle game. I did find the game’s plot and contemplations generally intriguing, but I was never under any illusion of who brought me to the party and I never really danced with anyone but her. I don’t think that I would play a “walking simulator” story-centric version of The Talos Principle and, similarly, I think that many other narrative skins could have worked for it. That said, the game is certainly successful in the narrative that it does present, and I hope to be even more intrigued by that of the The Talos Principle II.

CYBERPUNK 2077

As a long-time avid fan of Netrunner, the cyberpunk card game and greatest tabletop game ever made (Lotus Eater post coming 20XX), I was naturally excited for Cyberpunk 2077. I had been following its development with just as much breathless anticipation as everyone else, similarly dazzled by the promise of a wide-open cyberpunk RPG with an organic world and nigh-infinite options for roleplaying. I had not yet played a game developed by CD Projekt Red, but I figured that the positive reception to The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt was just further evidence that Cyberpunk 2077 was destined for greatness.15 By the time the game was set to release, I had lost much of that enthusiasm, however, as I had grown less and less keen on “open-world” or “sandbox” games. Its initial pre-release coverage was largely positive but it did ultimately just sound like cyberpunk Grand Theft Auto, and I… do not care for Grand Theft Auto. Even people who liked Cyberpunk suggested that it hadn’t meaningfully delivered on its promise of a deep and complex RPG and that it had only a shallow relationship with its cyberpunk themes. Then, of course, the game launched disastrously, and I was freed from the question of whether I would bother playing it.

Cut to three years later: Cyberpunk 2077 is good now. Or, so says the Videogame Press Industrial Complex, anyway. Truth be told, I’d been intending to play Cyberpunk 2077 for a while, long before it was “good.” At some point after the initial rancour had died down, I decided that I wanted to get in there and see for myself; no expectations, no hype, no stakes. I just wanted the opportunity to hang out in a cyberpunk-ish world for a bit, which is shockingly rare in videogames. I procrastinated this for long enough that eventually the much-ballyhooed Patch 2.0 was released and made the game, “good.” Regardless, I tried to keep my expectations in check, as I know better than to trust the gamerati (see Footnote 11) but I am happy to report that: Cyberpunk 2077 is good now. It was probably always pretty good, it was just in early access and had awful performance.16 Also, I don’t think it would have let me do a throwing-knives-and-hacking-only build before.

What’s strange about my experience with Cyberpunk 2077 is that basically every critique of it that has been mentioned thus far is true. It isn’t a very deep RPG. It doesn’t really engage that meaningfully with cyberpunk themes. It is essentially just cyberpunk Grand Theft Auto. And yet… I can’t help but feel charmed by the finished product. The world is so richly depicted, it is so utterly indulgent and resplendent with itself that there is a gestalt to the whole experience. It elevates what would otherwise be rote shallow repetitive gameplay (shooting, driving, fetching) to something far more engaging. Every scene in the game is dripping with this over-the-top kitschy attempt at cyberpunk style—none of the subtlety or deftness of a Bladerunner or Ghost in the Shell is to be found here—and yet the whole thing somehow works. Perhaps it is because this sort of ostentatious flimsy version of cyberpunk feels like something that itself would be produced by the cynical corporate-dominated world of Cyberpunk 2077. The player is constantly assaulted with some flavour(s) of cyberpunk; between the art, the dialogue and neologisms, the massive variety of advertisements and NPC barks and quests and neighborhood designs, Cyberpunk 2077 utterly force-feeds the player with its personality, fattening them up with seemingly-unlimited quantities of the richest sweetmeats. And even though so many of those calories are empty, the complete package still feels quite filling—at least for me and my little cyberpunk-starved brain.

None of this would work, however, without 2077’s glut of shockingly-competent writing. I do not mean to suggest that I am specifically surprised that CDPR are capable of competent writing—indeed, the things I liked most about The Witcher 3 were its quest design and dialogue. It’s more that I am not used to open-world games or “Grand Theft Auto-esque” games having competent writing. Typically, these sorts of games dispose entirely of careful, curated writing and direction, in favour of the buffet approach.17 All traditional narrative elements are sacrificed at the altar of the freedom to run around and do stuff and then are crammed haphazardly into cutscenes that are begging to be skipped. Not so in Cyberpunk 2077. Instead, the game presents a smaller, more curated selection of quests and activities to “run around and do.” The game never allows you to stray too far from something sort of “cyberpunk” and so ensures that the tonal and stylistic feeding tube never slips from your gaping maw. Woven throughout these activities are charming characters that I regularly found to be thoughtful, realistic, and compelling. I felt myself propelled to spend time with many of these characters—Jackie, Judy, Johnny Silverhand, Panam.18 19 I grew to know and to like them and I found myself wanting them to like me and to know that I had their backs. These are textbook parasocial relationships and if a game can produce those in you, then that, my friend, is a good game.

That said, Cyberpunk 2077 is not an excellent game. There are aspects of it that are excellent—some of which I have just discussed—but there are still some very notable and salient flaws. Chief among these is that this is an ostensibly-cyberpunk RPG where one’s only real solution for most situations is murder (or faux-murder). There is very little here in the way of traditional CRPGs or immersive sims; no, you will eventually (and often) just be forced to kill (or “kill”) people. Indeed, this makes up quite a large portion of the player’s experiences. There are a variety of options for how to kill, but the most prominent and strongly-endorsed technique is the most traditional one: shooting people. This is too bad, because I do not find shooting people to be an especially gratifying activity,20 and I do not find that 2077 presents an especially compelling version of it. The shooting feels bad, the gun loot system is silly and tedious, and enemies die far too easily from gunshots (at least on the default difficulty, they do). In order to ameliorate these issues, I quickly self-imposed a simple limitation: no guns. This instantly made the game far more compelling. Instead, I relied on a dynamic blend of stealth takedowns, hacking attacks and debuffs, throwing knife headshots, and, when all else failed, a humble katana. This made combat encounters far more interesting, enjoyable, engaging, and diverse.

The game also does not have anything especially interesting, novel, insightful, or nuanced to say about the topics typically covered by cyberpunk. Transhumanism is certainly an active force in the world of Cyberpunk 2077, but they don’t seem to have any particular perspective on it, one way or another.21 Cyberpunk presents a world that is run by multinational megacorporations. The game is clearly critical of this state of affairs but: What is to be done about it? What political and social forces allowed this to come about? What political and social forces might be able to bring about a new world order and what problems might that new world face? Cyberpunk 2077 largely avoids these questions, preferring the Ubisoft modus operandi of saying nothing and taking no stance on anything, ever. This does not damn the game entirely—as discussed, this sort of chintzy presentation works in its own resonant kind of way—but it does prevent Cyberpunk from reaching the higher echelons of the genre. Cyberpunk 2077 generally chooses bombast over nuance and sleekness over utility in a way that other cyberpunk games and media (e.g., the recently-discussed Citizen Sleeper) typically do not. But, ultimately, that’s okay. Bombast has its place. And its place is in my hastily-assembled 2023 GOTY list.

Final Considerations

It feels strange to write this Year in Review at all because it is mostly devoid of the superlatives that I would typically use to describe my favourite gaming experiences of the year (see Footnotes 1–4). I should probably entertain the possibility that my internal state and extraneous circumstances affected my perception of the year’s games more than they normally would have.22 I stand by my dramatic and extensive critiques of games like The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom and Final Fantasy XVI, but I cannot deny the possibility that I would have liked those games more if I had felt better at the time. So it goes. No aesthetic experience or critical reflection is immune to the vicissitudes of everyday life.

These effects are clearly demonstrated in the patterns of which games I played over the course of the year. In the first half of the year (while preparing for my defence), I preferred repeated, familiar, relatively high-effort experiences. For example, I completed a “Soul Level 1” run of Dark Souls 3, in which the player beats the entire game without leveling up past level 1. This was incredibly difficult but also deeply rewarding and, in my enervated state, was somehow less intimidating than just playing a new game. After completing that, I was still craving the comfortingly-desolate and familiar world of Dark Souls 3, and so I completed all of the remaining achievements in the game while watching bad movies on my second monitor.23 Other experiences in that portion of the year were very low-effort but were familiar and repetitive in a way that I found approachable and soothing: The Binding of Isaac, Halls of Torment, Vampire Survivors, Warm Snow. These sorts of games were especially attractive to me on the Steamdeck, at the time.

Later in the year, I seemed to prefer shorter, tighter, novel high-impact experiences more than I had earlier in the year. Those games are the ones you see mostly represented on this list here, but also include things like Apsulov: End of Gods (aborted because I did not like it), Touhou Luna Nights (fun game! cute writing and art!), and Returnal.25 I still couldn’t seem to stay away from the repeated, familiar, high-effort experiences though, as I also brought each of the classes in Slay the Spire up to the final ascension in difficulty and knocked out some of the game’s most difficult achievements. Throughout the year, I also dabbled more in emulation and old games than usual, thanks in part to the Analogue Pocket (which, technically speaking, is not doing “emulation”). This included revisiting one of my favourite videogame songs in Super Mario Land, playing the intriguing MyHouse.wad,26 and flirting with Golden Sun (Lotus Eater post coming 2002, written by a child).

There are also reasons for me to be optimistic about videogames in 2024. There are plenty of announced games that I will probably like: Final Fantasy VII Rebirth, Persona 3 Reload, Elden Ring: Shadow of the Erdtree, Metaphor: ReFantazio, Unicorn Overlord, etc. There are also undoubtedly many surprises in store that I will love. I will probably play Yakuza 3 and I will also probably play more decade-old puzzle games. More importantly, I will also do many things that have nothing to do with videogames whatsoever, and won’t that be nice? Plus, today I finally heard back from a Facebook account named Halo Wars whom I first messaged nearly five years ago. So, you know. 2024, here we come, and so on and so forth. Thank you for reading.

Footnotes

Compared to something like Inscryption, a game which demanded my attention and time so strongly that it could probably raise me from the dead.↩︎

The 2022 Lotus Eater Games of the Year: Elden Ring, Tunic, Neon White, God of War: Ragnarok, Fire Emblem: Three Houses↩︎

The 2021 Lotus Eater Games of the Year: Inscryption, Bloodborne, LISA: The Painful, 13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim, Dark Souls Remastered↩︎

Looking at my lists for 2022 and 2021 is both uplifting and depressing. I mean, damn, those are some of my favourite games of all time. It’s reassuring that I can still have those experiences reliably each year. But, on the other hand, nothing in my 2023 list comes close to the high points of 2022 and 2021. Even 2020—a year that we can all agree was lacking in most respects—offered me a GOTY list of absolute bangers (Hades, Final Fantasy VII Remake, Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice, Devotion). So it goes.↩︎

During a recent flight, after waking up wracked with a headache, I booted up a new file in Dark Souls and played through the first hour. Just for a bit of solace.↩︎

[threatening intonation]↩︎

Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice and, to some extent, Bloodborne are excused from this particular comparison. No game feels as good as Sekiro.↩︎

Hmm, it does not feel good to refer to the PS2 era as “retro.”↩︎

I realize that it likely did not actually invent this genre, but for many puzzle game neophytes, it may as well have.↩︎

First case achievement unlocked at 11:24 PM on a Friday night. Very unusual time to start a game. Final case achievement unlocked 1:56 AM on a Saturday night. This game was apparently not good for my sleep hygiene.↩︎

Not that there is any shame in using hints, of course. The best way to play a game is the way that one enjoys. But I do think that the pleasure and satisfaction of a game like Golden Idol is contingent on the player having a pure and unmediated investigative experience. The more you compromise that experience, the less satisfying it is likely to be. The only thing shameful in videogames is playing them at all and also perhaps liking a game like Red Dead Redemption 2. Thank you.↩︎

For other examples of this style of storytelling, please see Virtue’s Last Reward, Nier Automata, Undertale, and 13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim.↩︎

Even if it was clearly inspired by Myst, just like The Witness was.↩︎

Vampire Survivors also does this but in a much more wholesome way. It’s like going to a really ostentatious casino but only using fake money.↩︎

As it happens, I did play The Witcher 3 for the first time a couple of months after Cyberpunk’s initial release. I am, regrettably, a hater. I enjoyed some of the quest design and writing but I found nearly everything else to be slow and tedious.↩︎

Unfortunately its performance still leaves much to be desired, even on a relatively powerful PC. The game is also still by far the buggiest game I have played in recent memory.↩︎

I once cited this video in a textbook and I suspect that it is the only academic citation of Hey Ash Whatcha Playin’?. I have not looked into this, however, so please do not tell me if I am wrong.↩︎

It is extremely frustrating to me that Panam’s name breaks the alliterative chain, but she is far too roguishly charming to be omitted from this list.↩︎

My favourite questline was actually the one led by Delamain, an artificial intelligence that runs Night City’s most prestigious cab company. This series of quests was packed with moments that I found funny, touching, strange, and intriguing. Each time I expected it to do something boring or rote or repetitive or easy, the game did something interesting or surprising or delightful. The completion of this questline was probably the point at which I realized that I did actually like Cyberpunk 2077.↩︎

This is not a moral or political stance but an aesthetic one. I find shooting guns at humans to be largely unfun, unless there are other things bringing me to the party. I love the story and tone of Bioshock, and so I’m happy to shoot people there. I love the gamefeel and emergent narratives of Apex Legends and so I’m happy to shoot people there. I love the blistering speed and immaculate level design of DOOM (2016) and so I am happy to shoot demons there. But, generally speaking, I am not going to play a game if its primary promise is the opportunity to shoot a gun at people. And, although this stance is not moral or political, I will say that it did take me a little while to get used to committing mass murder with guns in Cyberpunk 2077. It turns out that if you avoid this sort of thing in videogames for long enough, you can sort of resensitize yourself to it.↩︎

Not that I am looking for a didactic or moralistic stance from the game. It’s just that the game as presented does not seem to really have anything to say about transhumanism at all.↩︎

Here are three other games that were strongly affected by my internal state and extraneous circumstances: Fable III (teenage breakup); Code of Princess (extraction of four wisdom teeth); Dreamscaper (general anguish). Thank you.↩︎

Super Mario Bros. (1991), Deadpool, Deadpool 2, Ant-man and the Wasp, Captain Marvel. This is why I keep a media spreadsheet, I guess. So that I will never forget that I rewatched the Deadpool movies while grinding in Dark Souls 3.↩︎

Please note that this is Champion Gundyr, and not Iudex Gundyr, who is the first boss of the game.↩︎

Returnal arguably warrants its own entry and quasi-review somewhere in this post, as I have a quite a number of Thoughts about that game. I originally started it several years ago, quite confident that it was going to Consume me, but I bounced off of it after 5 hours or so. At the strong encouragement of a friend, I revisited it this year and was able to push through the membrane that had originally repelled me. I am still very critical of the game in a variety of ways that said friend is not, but I definitely did enjoy the game a great deal more this time around and especially enjoyed playing it co-operatively with him.↩︎

Which, for me, made for a better video essay than gameplaying experience, but was fascinating nonetheless.↩︎