Hyper Light Drifter was released by the studio Heart Machine in 2016. It is a two-dimensional top-down action RPG where you play as a nameless wandering Drifter. He appears to be very ill—dying, perhaps—but is committed to carrying out some quest that is unclear to us, the player. The world he inhabits is one that is foreign and mysterious to us. No one speaks any language that we have ever heard, though they do communicate with the Drifter and he seems to understand. The world is filled with alien symbols, strange patterns, and arcane secrets—systems that might eventually cohere for the player, should we be sufficiently attentive and canny. Combat is incredibly swift but commensurately tight. The Drifter carries a sword, a gun, and is capable of (limited) dodging. This simple set of systems can prove challenging at first; movement is almost too fast and enemies seem to kill you with ease. It is worth overcoming though, as mastering the combat in Hyper Light Drifter is incredibly rewarding. Once you have a grip on these systems and on The Rhythm, combat encounters can provide the satisfaction of a souls-like and a shoot-em-up all at once. The game also happens to be very beautifully-drawn and animated and to have (what I consider to be) one of the best videogame scores ever composed. It is a very remarkable game for a great many reasons.

Heart Machine’s newest game is Hyper Light Breaker. It is none of those things.

CORRUPTION

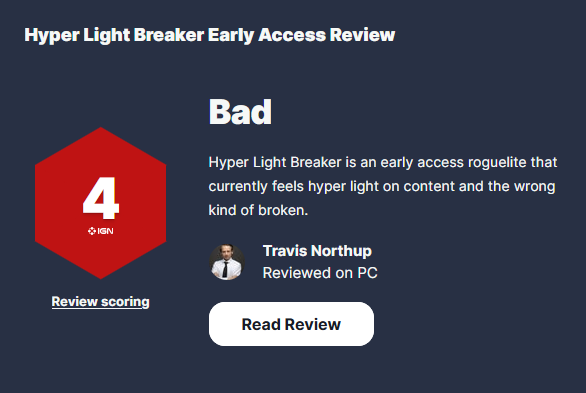

Hyper Light Breaker is ostensibly a prequel to Hyper Light Drifter, though not in any way that matters.1 It is a three-dimensional third-person shooter roguelike, with each run taking place on a new procedurally-generated map. The game is also multiplayer and co-operative, which is a first for Heart Machine.2 Currently, Hyper Light Breaker is in early access and still under active development, but coverage so far… has not been very positive.

In contrast with Drifter, Hyper Light Breaker has “sloppy combat mechanics,” “shallow and frustrating exploration,” a “micron-thin veneer of a story,” and is “bereft of the thrill that comes with uncovering hidden prizes in handcrafted nooks.”3 Of course, these reviews are based only on the early access version of the game, so it is all subject to change; except “its biggest issue is how that meaty part just isn’t all that enjoyable. The combat is awkward, the progression is doddering, and the world isn’t interesting enough to motivate indefinitely repeating visits to it.” Unfortunately, none of this came as a great surprise to me.

CHIMERA b/w CULT OF THE ZEALOUS

Heart Machine made one other game after Drifter and before Breaker. Solar Ash was released in 2021 and shares little mechanical resemblance to either of the Hyper Light games, though some visual resemblance to Breaker. It is a three-dimensional third-person game in which you rollerskate-explore an alien world, engaging in some light combat and platforming along the way.4 There is almost nothing substantial in the way of puzzles, progression, or collectibles—certainly not compared to Drifter—and so the game’s main offerings are its movement, its story, and its art. Fortunately, I can tell you that the movement in Solar Ash is excellent. It feels remarkably good just to surf and jump and grapple around its colourful biomes. Unfortunately, there is absolutely nowhere of interest to go and absolutely nothing of interest to do. The combat is rudimentary and awkward, the sort of thin fare you would expect from a low-budget 3D game, perhaps, but not from the developers of Hyper Light Drifter. The story is similarly-thin at best and painfully-bad at worse—and it is often at its worse. The dialogue smacks of Intro to Creative Writing and is only further hampered by the shockingly-bad voice acting.5

It should come as no surprise that this was incredibly disappointing for me. I adored Hyper Light Drifter and I was extremely impressed with the ambition on display in Solar Ash’s trailers. I knew that the transition from 2D to 3D could be monstrously difficult—likely insurmountable for most indie devs—but I had little doubt. Drifter was an essentially-perfect execution of a singular coherent vision that rang out in clarion clarity. The team responsible for it wouldn’t move to 3D unless they had good reason to and were absolutely certain that they could find similar success in that added dimension. I eagerly awaited the game and even played it the day it released, something that is surprisingly-unusual for me. Here is a brief selection of messages I sent that day:

solar ash not releasing until noon. stupid. bad6

wow disasterpeace didn’t do the music for solar ash and it’s instantly noticeable. how deflating7

played the first hour of solar ash today. honestly… doesn’t seem great!

navigation in solar ash fucking rocks. just moving around feels so cool (except that there isn’t an air dash despite me trying to air dash constantly). but there is no reason to move around because the rest of the game isn’t compelling.

it’s not an awful game8 but it’s shockingly not that good and what’s particularly surprising about it is that most (all?) of its weaknesses are the strengths of hyper light drifter

Unfortunately, time did not soften my opinion of Solar Ash. My notes/messages/tweets from my time with the game are filled with gently-devastating critiques that still hurt to read, even three years later:

this game cannot seem to figure out what is good about it and it just kind of makes you run around hopelessly trying to find it.

it’s hard to believe that this is from the same developer as hyper light drifter: the tight combat, gone; the secret hunting, gone; the immaculate tone, gone; the experimental storytelling, gone.

i’m only a few hours in so maybe i’ll turn around on things. i hope i do! but right now this game consists solely of a sequence of dull chores strung together with excellent movement and the occasional cool platforming sequence. which is simply not enough to carry a game for me.

Incredibly repetitive, but also the thing it repeats just isn’t that good. The navigation is fun but it seldom leads you to anything fun. The main task you complete is fun enough the first time but not the countless times afterward. The combat is just awful, the game would be improved by removing it wholesale. The secret hunting of the first game is completely gone. So is the subtle experimental storytelling. It’s replaced with obvious self-evident “secrets” and overly-verbose boring Proper-Noun-Laden “tell don’t show.” The music is also extremely spotty, ranging from bad to fine (with the exception of the couple of Disasterpeace tracks). I have so many complaints! It was so bad!

…what happened?! It’s like this was made by a completely different team from Hyper Light Drifter. Everything good about HLD is awful in this game. It’s like they learned all the opposite lessons from their own game.

WISDOM’S TRAGEDY

I posed that question to myself—what happened?—in a spreadsheet in December 2021 and I still do not have a good answer, though I have some guesses. I am not a game developer but I have tried to familiarize myself with the processes that it entails and, whenever necessary through ignorance or humility, I try to defer to the fact that: making games is hard. I do have some experience with pursuits both artistic and techological and I can imagine that trying to innovate in both domains simultaneously would be uniquely and especially difficult. Solar Ash strikes me as being the victim of unchecked ambition, ambition that was not matched in resources, expertise, or ideas. As intimated previously, making 3D games is a very different hunt from making 2D games, and the beasts are surprisingly dissimilar. Processes that seem deceptively-simple in 2D games—like movement, like asset generation, like player perspective—become undeceptively-complex in 3D. Skills honed in 2D game development may not always transfer smoothly to the new dimensions and, even when they do, some tasks will still naturally and necessarily require more time or more people.9 This can often make the process more complex, more expensive, and laden with all sorts of hazards and risks that you might never have encountered in 2D game development.10 To put it bluntly: I suspect that the team may have written a cheque that they were unable to cash.

The one idea that Solar Ash did have—rollerskating around an alien world—was competently-executed, all things considered. Heart Machine just did not seem to know what to do with that idea. No other aspect of the game had the heart, personality, or passion that had clearly gone into the game’s movement. The story, the world, the characters, the music, the combat—it all felt phoned in to support the game’s singular offering. Even the boss fights, something that should make use of Solar Ash’s movement, were repetitive and staid.11 The juxtaposition here with Hyper Light Drifter is starkly unfavourable. Every single moment of Drifter feels carefully-considered and lovingly-executed. Every inch of its map is teeming with secrets, both mechanical—hiding one of the game’s dozens of collectibles—and narrative. The world of Hyper Light Drifter is mysterious but it has such sights to show you, for those willing to look. Its architecture, its wildlife, its abandoned technology and barely-surviving inhabitants; they all cohere to create a uniquely-beautiful tone, at once melancholy and wondrous—and all without (human) language. There is no such passion or care evident in Solar Ash. There are no secrets to glean, there are no stories to uncover, there is no truly-alien world to discover. There is only rollerskating and even that loses its appeal after like 20 minutes.12

A CHORUS OF TONGUES

My experience with Solar Ash had left me crestfallen. I had not lost all hope in the studio but I was (and remain) confused as to exactly how they had managed to make a game that failed so precisely in all the ways that their first game had succeeded. It felt like they had been the victim of some cruel monkey’s paw curse, and when Hyper Light Breaker was revealed in 2022, another finger curled. Here was a game that ostensibly returned to the world of Hyper Light Drifter but relied on the systems that had been developed for Solar Ash. It was 3D, yes, but even more notably, its world would be procedurally-generated. For the unititated, procedural generation is the process through which a game can create “new” content—usually levels—according to some set of principles and rules. Thus, rather than handcrafting bespoke levels designed specifically to interact with the player’s movement and combat abilities, levels can be created endlessly but are typically more generic and more utilitarian.13 This felt like another sound rejection of the philosophy that guided Hyper Light Drifter: the world would not be a deliberately-crafted diorama designed specifically to tell a particular story, convey a particular tone, or even create a particular combat scenario.14 It would be loops and iterations and meditations on a handful of rules, endless recombinations of the same handful of lego pieces jammed together to give the player Endless Grinding Runway.15 When I saw the game presented in this way, I knew in my heart that it was Not For Me and, perhaps, Not For Anyone.

It wasn’t necessarily going to be that way, of course. My predictions are often wrong.16 This does not appear to be one of those cases, however. Basically all coverage of the game’s early access has been thoroughly negative and even fans of the studio do not seem to like it. The game seems to struggle in many of the same ways as Solar Ash, with “lackluster hack-and-slash combat,” boss fights that are “downright annoying,” “interfaces and item descriptions in plain English” that “chip away at the otherworldly vibe,” and music that “isn’t as evocative and atmospheric [as that of Hyper Light Drifter].” Even the movement seems to have worsened since Solar Ash—likely because of the procedurally generated levels—with maps that are “extremely obnoxious to navigate, filled with awkward cliffs and crooked landscapes that feel like I’m not actually supposed to be climbing them but offer me no other choice.”17

PANACEA

I hope that they are able to amend this, of course. I take no pleasure in beholding the struggle of a studio that produced a game I so adored. To the outside-observer, however, Breaker’s development has been troubled: the relase of its early access was delayed by about 18 months and it still launched in a state that is reportedly both broken (which is probably fixable) and unfun (which is probably not). The studio also reported layoffs last year and one imagines that this rocky launch will not make things easier for them. I genuinely do hope for the best for them though. Although I am in some ways a dyed-in-the-wool hater and am on the record as being quite scornful towards some massive AAA games, I am unreserved in my praise for interesting and subversive indie games. Please do not mistake my disappointment for antipathy, nor my protracted contemplation for derisive revelry. I hope that Heart Machine are able to get Hyper Light Breaker on track and, even more than that, I hope that they are able to implement lessons from its (and Solar Ash’s) development in future games. They might also find use in adapting some of the lessons and design philosophies found in other games; might I recommend Hyper Light Drifter?

Some final errant thoughts:

Each chapter of my doctoral dissertation had an accompanying song selected from a videogame score. The song accompanying Chapter 2 was Disasterpeace’s A Chorus of Tongues, from the Hyper Light Drifter soundtrack.

The first trailer for Hyper Light Drifter featured a song by one of my favourite musicians, Baths. Despite preceding the game (and, presumably, the game’s actual score) by several years, it’s a remarkable synthesis of Disasterpeace’s eventual work on the game and Baths’s unmistakable songwriting style.

Solar Ash was originally announced as “Solar Ash Kingdom.” I am of two minds about this change of name. On the one hand, Solar Ash is probably a better, pithier name. On the other, I appreciated that “Solar Ash Kingdom” had the same meter as “Hyper Light Drifter” and, given my love for structural symmetry and rhythmic patterns, I delighted in the idea of Heart Machine releasing several games with this naming convention. In the end, it’s probably for the best that the name was changed and the game was distanced a mite further from Drifter, given how unfavourable direct comparions with that game already are.

Thank you to James Archer and Travis Northup, both of whose coverage of Hyper Light Breaker is heavily-quoted in this text.

Footnotes

At least not to me, a person who adored the story of Hyper Light Drifter.↩︎

Techically, a local two-player mode was later added to Hyper Light Drifter, but.. you weren’t going to mention that, were you? No.. no, I didn’t think so.↩︎

These quotations are all lifted from the IGN and Rock Paper Shotgun reviews linked in the main text.↩︎

I rewrote this sentence several times to make it as balanced and neutral as possible, ridding it of all scorn while still saying something that is meaningful and correct. It is not a very good sentence.↩︎

This point warrants some elaboration. I do not consider myself to be an expert in evaluating voice acting but I am also not especially critical of it. I seldom find myself bothered by voice acting (even when it probably is poor), despite having played plenty of JRPGs in English (which have something of a bad reputation). That said, there have been a handful of games (or even just singular performances) that I found to be so grating or unnatural that I would literally and physically cringe in response to them. Solar Ash is one of the more memorable offenders in this regard, although I suspect that it was a writing × performance interaction, each making the other seem worse than they would have otherwise. This is an utterly unforced (and expensive) error. Some games—really only a handful, in the grand scheme of things—necessitate voice acting. Other games benefit from it (or would benefit from it, as the case may be). Solar Ash falls into the third category: games that are categorically-worsened by voice acting. The weak, unconvincing performances serve only to remind one of how thin and inorganic the world and its story are. Characters that already feel lifeless and flat dribble forth performances that are, perhaps unsurprisingly, lifeless and flat. The world, clearly-intended to feel alien and foreign and solitary, is rendered banal and quotidian by its sophomoric writing and awkward performances.↩︎

In case the tone of this first message is ambiguous, let me clarify: I was excited to play the game and was feigning petulance about it releasing so “late” in the day.↩︎

This one still stings. As mentioned in the opening paragraph of the main text, I consider the score of Hyper Light Drifter to be among the greatest in the medium. The composer, Rich Vreeland (aka Disasterpeace), had been similarly successful with his excellent score of Fez, but had a uniquely-disproportionate influence on the tone and feel of Drifter. His music was synonymous with and inextricable from Hyper Light Drifter. When I recognized his unmistakable sonic signature in Solar Ash’s trailer, I was further reassured that the game was destined to be something special. I had been the victim, unfortunately, of a little trick: Disasterpeace had only composed a few songs for the game and the player seldom encounters his music. I will refrain from speaking too negatively of the music that was in the game as my impression of it was deeply impacted by both unfulfilled expectations and unfair comparisons but, suffice it to say, I was not impressed with the ersatz Disasterpeace. Others appear to have similar concerns about Hyper Light Breaker.↩︎

Further exposure actually led me to revise this perspective; it is an awful game.↩︎

This is not to say that 2D games are “easier” to develop, per se, but speaking in the broadest terms… they are often simpler to develop. Your brain is now resisting this sort of broad and general observation and is automatically generating counter-examples. That is fine, just relax and let it happen. It is all part of the Blog-Reading Experience.↩︎

If you would like additional evidence of this claim: Solar Ash was dogged with performance issues, even on the PS5, and still performs poorly to this day. Hyper Light Breaker is reportedly even worse in this regard.↩︎

This was another real pit in my tart: every boss fight was a slight variation on the first. I remember fighting the first boss and thinking “Oh, that was sort of fun, if a little tedious. I hope I like the next one more!” My hopes were dashed though when I fought the second (and the third and so on) and realized that these bosses differed only in slight superficial ways and in the precise amount of tedium they comprised. The boss fights are clearly meant to be reminicent of the beloved PS2 game Shadow of the Colossus, but they have none of the thrill, scale, and variety of those fights. In this regard they break a cardinal rule: never remind the player of a better game they could be playing instead.↩︎

One final thought on Solar Ash: I have stated in no uncertain terms that I found the writing to oscillate between impotently-dull and violently-bad. Hyper Light Drifter, on the other hand, has no writing—or, rather, it has no “writing.” The game communicates only in strange symbols, sounds, abstract visuals, and environmental clues. I originally found this to be deeply impressive—and still do, in most respects—but Solar Ash did lead me to re-assess it, to a certain extent. To what extent did I find profundity in what was mostly bluster and static? Was I finding signals and patterns where there was only noise? It didn’t really matter, of course, so long as I (felt like I had) detected those signals and patterns. I do think now though that Hyper Light Drifter was making use of the old proverb: even a fool, when he holdeth his peace, is counted wise, and he that shutteth his lips is esteemed a man of understanding.↩︎

The topic of procedurally generating levels is beyond the scope of this article but, speaking in the broadest terms: it tends to work much better in 2D than in 3D. Some games rely on it through necessity, neither implementing it in an especially-interesting manner nor suffering from its usage (e.g., Hades). Other games communicate their personality and tone in part through the procedural generation (e.g., The Binding of Isaac). Perhaps the most well-known and well-liked example of it is the Diablo franchise, whose entire gameplay loop is built on repeatedly exploring different iterations of the same maps. What unites each of these examples is that they are 2D games and what sets Diablo apart from most other games is that it is developed by a company worth many billions of dollars.

Procedural generation of 3D levels is somewhat less common and tends to be somewhat less memorable. There are, of course, plenty of examples—they just usually come with some caveats. Minecraft procedurally generates its worlds but those worlds are not exactly known for their charm and personality. They are there to serve a purpose and being constructed using voxels makes them a somewhat more straightforward affair. Minecraft also happens to be developed by a company worth many billions of dollars. No Man’s Sky procedurally generates its infinite planets but was also infamously empty, dull, and lifeless when it first launched. With years of additional post-release development, the procedural generation appears to have gotten to a place where it can create interesting and worthwhile worlds, but this is clearly an extreme and unique instance. Usually, you get games like Necropolis, which made the unbelievably-compelling promise of an infinite souls-like but ended up just reminding everyone of why the level design in FromSoft games is so good and probably handcrafted for a reason.

None of this is to say that procedurally generating levels is a Good Idea or a Bad Idea. It is a tool and can be an incredibly-useful one given the right project and the right craftsman. However, I do think that some developers are beguiled by the promise of Infinite Content, not realizing that most games succeed by providing handcrafted, carefully-directed and bespoke levels, and this is especially true for games that rely heavily on movement.↩︎Lest I sound overconfident in this prediction, I present you with another withering quote from Rock Paper Shotgun: “But as a gamespace, it’s nowhere near as storied and explorable as Drifter’s post-apocalyptic warrens. Half the fun of that game was poking around for its secrets, uncovering tunnels and treasures that a less curious nose would never sniff out. Hyper Light Breaker’s rewards and collectibles are kind of just… lying there, out in the open. Usually with a map marker pinpointing their exact location, and/or inside a copy-pasted structure that you’ll have visited in a previous run. It’s open-world map design the Starfield way: technically unique, but bereft of the thrill that comes with uncovering hidden prizes in handcrafted nooks.”↩︎

This likely sounds more negative than is intended. I (sometimes) love the Endless Grinding Runway! I just think that it is the diametric opposite of Hyper Light Drifter and what made it so great.↩︎

I was certainly wrong about Solar Ash!↩︎

Again, these quotations are all lifted from the IGN and Rock Paper Shotgun reviews linked in the main text.↩︎