It was a strange year for videogames. And, by “strange,” I mean “bad.” I don’t really mean that, probably—there are great games coming out all the time, many of which we do not even know to anticipate—but there are waxing years and there are waning years and I feel reasonably confident in saying that there was not a great deal of moonlight this year. 2025 saw the release of a Monster Hunter, a DOOM, and a Nintendo console, and no one seems all that thrilled about any of them. There were surprise hits, of course—Blue Prince and Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 to name two of the biggest—but even those seem to pale in comparison to the hits of recent years.1 For this reason, I was especially curious about the recent gaming experiences of this year’s guest contributors and their thoughts about the current state of the gaming landscape. It turns out they were mostly playing stuff like Mega Man Legends and a Final Fantasy IV romhack. Fair enough.

As with last year, I put minimal constraints on these guest posts and, also as with last year, I was very pleased to see people handle them in a variety of ways. It brings me a deep and perverse pleasure to see that there are only a handful of games from 2025 even discussed throughout these posts and was particularly glad to see a few games that were completely new to me. Whether this ratifies my claim that 2025 was a middling year for games or is simply evidence that I keep irreverent company is a matter of deliberation for the esteemed reader alone. I was also pleased to see two returning contributors, both of whom will be receiving their Lotus Eater Challenge Coins in the mail shortly.

Thank you to everyone who contributed to this year’s guest post. I deeply appreciate you sharing the precious meats of your thoughts and I will do my best to protect them from the roving gangs of starving AI cyberbeasts that lurk just outside the reach of the Lotus Eater firelight.

CULTIVATING TASTE

Contributor: DKMode

As far as media consumption goes, the past couple years of my life have been occupied with trying to intentionally develop my taste. For someone who has worked in the games industry for a decade, there is always a temptation to Keep Up; know what’s coming out, know what people are talking about, play and have a Take on them, think about what to steal from the good ones, and so on. This has led me to having generically Good Taste, and playing a lot of games that feel good in the moment but are ultimately forgettable. By contrast, my coworkers are largely Artists and have much more specific taste which leads them to discover really obscure and interesting work. That seems like a much more fun and fulfilling existence and thus is something I have actively been trying to cultivate for myself.

This is a long-winded way of explaining why there are few games released in 2025 on this list.

FINAL FANTASY IV (NAMINGWAY EDITION)

Y’all heard about these Final Fantasy games? Pretty good. Me, I was a perennial Sega kid so I fully missed every JRPG–I was not hip enough to know what Phantasy Star was—until Grandia II (goated). So I’ve been slowly picking my way through the classics.

As far as the SNES games go, FFIV tends to get overshadowed by the systemic complexity of V and the storytelling ambition of VI, which overlooks how much experimentation Squaresoft was doing here, both in the first appearance of the ATB system and the exploration of what you can do with storytelling using the tools available to you in the JRPG format. I was most impressed by its use of diagesis; character abilities in battle carry over to what they can do in the story and vice versa. This is a game that considers a character class not just a series of combat skills but an expression of how that character fits into the world. As an example (and one with some spoilers, so warning if you’re sensitive to that kind of thing): Rosa is not just “a person who can heal”, but someone who actively learned how to become a White Mage in order to support her boyfriend Cecil, who himself has taken on the burden of being a Dark Knight to protect his kingdom’s royalty. A royalty that does not care about the physical toll it takes on him (literalized in-game by his unique ability being a powerful multi-hitting attack that also damages him, and gets less useful as the game progresses), and ultimately requires him to ascend beyond it, literally changing his character class to navigate his new reality in a way more reflective of how he wants to move in the world. I don’t think I’ve seen any RPG with so much focus on this in-or-outside-of Final Fantasy. It’s something special.

I’ve noted the version of the game I played in case you too want to play it for the first time, because for these older Final Fantasy games, this really matters. Famously, this came out as Final Fantasy II in North America, and with many fundamental changes–not just localization quirks but sweeping changes to balance, maps, and mechanics. This fan-made romhack gives you an English version of the game that matches with the original design, while maintaining the tone and peculiarities of the Ted Woolsey translation–a part of Final Fantasy’s history and one worth experiencing in my opinion. If you want to know more about the various versions of classic Final Fantasy games, I highly recommend AustinSV’s excellent deep dives. It’s pretty wild.

CONSUME ME

A wonderful, funny game about a dark subject–disordered eating–which fully confronts the bleakness of that behaviour without ever becoming morose about it. It never looks at you and asks “hey this is really fucked up, right?”. It just displays the behaviour and if you’re a person who has lived in the world for long enough you can recognize how unhealthy it is. I find this very respectful of the player and everything supporting the core narrative of the game is extremely well-made. A bunch of solid minigames and the time management aspect is so fun to mull over that it made me furiously look up other games like it (which I learned are mostly unavailable in English, depressingly).

The whole thing also wraps up in a very sweet and lightly meta way that I was conflicted about initially but grew to really like. If I had to pick one Actual Game of the Year, it’d be this one.

OF THE DEVIL

If you like the Ace Attorney games you’ve simply gotta play this. Those are defined by being charming as hell but sorta creaky to play. It’s easy to get stuck not knowing where to go in the investigation phases, and to know the solution to a puzzle but not how the game wants you prove it in the trial phases. They’ve made various changes over the years to make it smoother but I don’t think they’ve ever fully figured it out.

Of the Devil takes a very endearing swing at iterating on those mechanics by making the possibility space smaller, and by giving you an optional reason to try to get the logic right on your first try (more credits that you can spend on fun bonuses!). It then wraps all of this up in striking character design, sharp UI, a neat cyberpunk setting, and a central gambling metaphor that ties the whole thing together.

This is still coming out, with the first two episodes out already and a third in a couple weeks, so the caveat is that it’s possible they’ll totally biff it as they go on, but with how strong the first two episodes are, this seems highly unlikely. Episode 0, the first one, is free, multiple hours long, and extremely recommended.

ANTHOLOGY OF THE KILLER

Nine short related games bundled together with some bonus features and an interactive wrapper. I find it hard to write about—it’s a series of alt games that mostly involve walking around a space and reading text until something happens. The details are what make it work which means it can be tricky to make an outright pitch for it. What is most unique about it is its specific approach to horror-comedy, which is to always no-sell the horror. The world of this game is one where the prevalence of various types of killers is comically high. A person you knew getting killed in some fantastical way is about as mundane as the weather changing. It’s a thing that happens and that you expect to happen to you too, probably pretty soon. Killers are so common as a cultural identity that there are bands and zines about them. Obviously this is pretty loaded and there’s a world where the game is really annoying about making the connections to our real world, but by way of being several games that were made over a few years, it has a lot on its mind beyond the core satire. Each game has its own focus and angle on the core themes, as well as some new storytelling presentation. Those themes are: the horrors that unfold around us and eventually come to bear on us as we try to live our daily lives, the hero worship and in-fighting of weird small art scenes, and the inescapable frictions of modern physical spaces being built on the bones of older ones.

Lest you think this is some heavy art game, it is also incredibly funny. I’ve probably taken more screenshots of random bits of this game than anything else in the past 5? 10? years. It’s got a lot to mull over if you want to, but it is a joy to do so, and with how short the whole thing is (you’re wrapped in ~4 hours), I can see myself revisiting it yearly.

SLAY THE SPIRE

You probably know about this game and have put hundreds of hours into it. I got back into it this year, in the hopes of finishing Ascension 20 with every character before the sequel releases. Thank you Mega Crit for delaying the game, giving me a few extra months to wrap it up.

Every other roguelike deckbuilder walks in Slay the Spire’s shadow and even the best of them pale in comparison (fwiw, my favourite non-StS one is Cobalt Core, which is different enough to be satisfying on its own terms). I wanted to spend a bit of time unpacking what makes it so good.

Slay the Spire is a game that you go through phases with. Initially you’re you’re learning the mechanics, unlocking each character’s full kit and then working to finish a run with each of them. Push forward and you enter the middle period, which I have to admit I struggled with for a long time. Here, it can feel like success depends more on getting specific good tools on a run than your own ingenuity. You chance every event and save scum it if you don’t like the result. This is where the game can feel its most grindy, but if you get through it you get to late-game nirvana. You know the game well enough to know which challenges you’re going to face in each act, and you start building towards those rather than just taking good cards. You see how cards that seem bad at the outset are incredibly strong in certain situations. You think about your HP as a resource, you take calculated risks, you think a lot more about pathing. You roll with bad choices to see if you can pull your way out of them. You notice just how possible it is to put a successful run together if you can only recognize the pieces. The game is open to you, and you will probably play it forever.

Other deckbuilders and roguelikes can’t match the way StS stays fulfilling at all phases. Even at its grindiest, all it takes is one revelation, and the revelations come quickly. Every time I consider whether I’d rather put time into some fresh roguelike deckbuilder or StS, the answer has consistently been Slay the Spire. That is likely to continue to be the case until the second one comes out.

While I’m here I have to get something off my chest. It is somewhat common for players to complain that Slay the Spire is aesthetically weak. I think this is insane. The visual design of the character classes is immediately iconic with striking silhouettes and a unique otherworldly style. Enemy designs intuitively contextualize their attack patterns. But we gotta talk about the actual cards.

Card games are cool because the cards are symbolic. They represent you doing something, and they do this through a combination of a name, an image, and some text. Card games are at their best when these three things work in tandem to give you a clear idea of what playing the card is doing in the world of the game. In Slay the Spire this is always the case. Switching stances, throwing shivs, parrying enemy attacks, making demonic pacts with ritual swords, rewiring your own circuitry–this is all stuff that you can do in the game and that feels like you are doing it. That is more than just pure mechanics and numbers; that’s aesthetic strength. It drives me actually crazy that people will say this game looks “bad” and then point to Monster Train (a game I like!) and say that its knock-off Hearthstone aesthetic and floaty autotweened animations look good. Get real!

HONORABLE TENSIONS

Contributor: bigsquishyfrog

HOLLOW KNIGHT: SILKSONG

Despite a trending desire for “shorter games with worse graphics,” it is hard to say that industry development or playing practices have at all shifted. Infinitely-replayable roguelikes and massively padded campaign-games still dominate the new releases, and the charts are topped by the same-but-different battle royales and ranked games as years past. Yet, a new sentiment emerges that a video game should “respect a player’s time,” which I largely agree with, even if the notion crumbles if you spend just a couple seconds reflecting on what a massive waste of time playing video games actually is. Our time is more precious than ever, and our attention is a resource, so god forbid our toys deprive us from dopamine or progression for more than a couple seconds.

It’s a bit of a paradox. We long for difficult games, but we don’t mean short punishing ones like NES games. We want to lose, but for that process to be so elegantly crafted that we don’t feel the consequence of our failure. Above all else, we absolutely do not want to sit controller-in-hand but without player control, or to replay a part of the game that we’ve clearly already bested. I don’t predict anything to come out of this tension. Games will become even more polished, have their corners rounded even more, each one a better theme park attraction than the last. But that was bound to happen.

Anyways, I didn’t play Hollow Knight: Silksong in 2025. I did play Blue Prince. It’s a great game, but seeing the same three-second cutscenes play out each run annoyed me terribly.

THE BAZAAR

There are fun games, and there are games I want to play. The Bazaar is both, which I congratulate it for. It is an asynchronous autobattler PvP tableau builder with heavy randomness and drafting mechanics, or as a comparison, something like Super Auto Pets meets Slay the Spire. In the year since release, it has struggled to find a steady footing. It has a modest but fervent player base and I’ve lost track of the number of monetization models they have tried out. The game is missing some seriously basic features that would serve it well: there are no social features, no match history, no mobile release, and QOL updates come in at a drip-feed. I say all of this to give more weight to my recommendation. It is a very good game. If you enjoy card-ish strategy games, please give it a try.

I am often cynical towards skinner-boxy casino games, but I think to criticize The Bazaar for employing RNG so heavily would be to detract from the depth and character of decision-making that they’ve embedded into the game. Generally, the only actions a player has in game are to buy items, sell items, and move items on your board. Fights play out completely automatically. If you are unwilling to pivot your build or try fringe strategies, the game probably resembles a slot machine: reroll the shops and get a dopamine hit when you find the item you want, cry if you don’t. With some familiarity with the items and mechanics in the game, it’s actually a very strategic system that requires you to develop a learned intuition about the relative strength of your board compared to other players.

One of the core tensions, for instance, is whether you should play greedily in order to maximize your chances of winning the next fight, or instead invest in resources that will be even stronger in later fights. Another is a macro rock-paper-scissors battle mechanic between build types: weapons beats poison, poison beats shield, shields beats weapons. But the combinatorial nature of your boards allows you to hedge instead of full-committing, and the “enchantment” system allows you to, say, turn a high damage item into one that heals or vice versa. All the while, the micro decisions of placing your items on the board for maximum value through adjacency mechanics, deciding which of two “medium” sized items are better for those last two spots on your board, etc., remain interesting and engaging.

It’s possible The Bazaar will go down as “that one game Reynad made” or “that one game Northernlion kept complaining about,” but I hope for its sake it doesn’t. It’s a mess of a game, but a pinnacle of both the autobattler and card strategy genres.

THREE OTHER GAMES

Short comments for the three other games I played in 2025:

Logic Bombs is a tightly designed Picross-style logic game by games essayist Matthewmatosis. It is unabashedly minimal, opening with a remark that the game contains no metagame puzzles that have somewhat become an expectation of the puzzle genre. Gracefully difficult and simply enjoyable.

Dustforce is a 12-year old precision platforming score-attack game that I have finally played after listening to its amazing soundtrack about a hundred times. It plays like a dream, and I think in some alternative universe, this would have been the poster-child platforming gem that everyone tries to make copies of. It holds up beautifully, and I hope the Hitbox Team someday dusts off the old computers to treat us with something new.

Nuclear Throne received Update 100 this year, its first in 8 years. I feel like Vlambeer were some of the early proponents of “gamefeel” and “juice”, and I think Nuclear Throne is a great demonstration of what it means to do that right. It is incredibly snappy and reactive, and it’s certainly because of more than just particle effects and screenshake.

THE ARTIST’S FINGERPRINTS

Contributor: psionic_warrior (twitter, bsky)

The theme of 2025 globally was slop. I don’t just mean actual AI-generated slop. Something can be slop even if it was made by an earnest, talented team of professionals. I mean slop as in, this piece of media is soulless. It’s safe, it’s well-executed, sure, but it’s slop. Gacha games with focus-tested fertility idol anime girls. Extremely technically proficient TikToks of people painting scenes from Skyrim. Everything that is conveyed by the term ‘Reddit.’

One struggle our current moment has is that it can’t really fight AI. Most of us don’t really like interesting or thought-provoking art. We don’t have any natural defense against slop. I’m not immune to this. I have a deep embarrassing love for Tom Clancy-level airport thrillers. Many people I respect also suck down slop. I’ve seen many sane, highly intelligent adults claim to enjoy Baldur’s Gate 3.

My point is, most of my media diet is made up of things that aren’t very good. Most other people’s are too. What this means is that when there actually is something that breaks through the sea of slop, we have to hold it dear.

In painting, the technique of ‘impasto’ refers to artists using the intentional over-application of paint to achieve a textured surface, which has all sorts of various artistic effects. One thing that’s always stuck with me in learning about this, is that in some art that uses impasto, the artist would apply the paint with their hands, and art scholars centuries later were able to do deep scans of that paint and actually extract the artist’s fingerprints.

To me, good art is art where you can see the fingerprints. I have far more respect for an artist that’s trying and failing to get something across with intentionality, than I do for an artist that looks good and says nothing.

AI, of course, is the peak of ‘looks good and says nothing.’

There’s really only one game in 2025 where I saw the fingerprints.

DEATH STRANDING (2019)

I had originally bought this game when I bought my PC in 2021, played about five hours of it, got bored/frustrated, and quit. I imagine that’s what the average gaming consumer did too. To be fair to gamers, it doesn’t show a very good side of itself, initially. The first 5–10 hours, which makes up the initial ‘tutorial’ area, has a completely different gameplay rhythm and structure than what you’ll be doing for most of the game. Once you can get past that initial tutorial, the game opens up and is a lot more fun.

Lucky for me, I was able to skip the tutorial this time by virtue of playing through it in 2021. So what makes Death Stranding so compelling? Well, the key is that you have to walk everywhere.

In Death Stranding, absolutely no aspect of the gameplay experience is abstracted away. If you want to go somewhere, you have to walk, or drive, or ride your trike. If you want to add something to your inventory, you have to physically carry it somewhere. This new item takes up actual game-space. If you want to carry a lot of things? Well, you’re going to need to think up some solutions.

That means, when you want to do something like build one of the game’s massive megastructures, you’re engaging with every part of that. You’re the one working out where to source your ceramics, how to get those ceramics to where you need it, and actually going through the gameplay of taking it there.

Same thing with combat. There are no generic enemy NPCs that you can just waste; every enemy killed represents an actual human life lost in this world, where that loss of life can mean anything from a major inconvenience to a major disaster. You have to step lightly, use non-lethal tactics, and accept that your options are going to be limited.

All this is augmented by what is actually the game’s marquee mechanic: structures built by other players in their world will show up asynchronously in yours. You might be running out of battery in your truck, just to see a recharger past the next summit. A previous player may have put up fixed ropes on a difficult mountain climb. You can use zipline pylons placed by others to build out your own network.

This shifts the entire dynamic of the game, from something that might feel deeply lonely and alienating, to a game where you feel connected with others. Best of all, since all the help you’ll be getting feels very altruistic, you’ll start feeling altruistic yourself as well. This creates a natural harmony between the mechanics of the game and the themes of the plot.

Very few games I’ve played, before or since, have been designed with that level of intentionality. Sometimes, this results in something that’s maybe a little annoying, or tedious. Mostly though, it’s something totally unique.

Honorable mentions to games like Final Fantasy VII Rebirth, Like a Dragon: Infinite Wealth, and Deltarune, which I also played and enjoyed a lot in 2025, but were respectively too messy, too annoying, and too unfinished to be my GOTY.

ACTUALLY THE BEST GAME OF 2025

IS ON THE PLAYSTATION 1

Contributor: Zack P (partner’s instagram)

Mega Man Legends (which I will refer to as Legends henceforth) is a semi-open world 3D action RPG for the Playstation 1. And I can’t shut up about it. Now it’s your problem.

DUNK ON YOUR CHILDHOOD

When I was a child, I owned this game’s inferior port on the Nintendo 64. I didn’t get very far, and had a dim understanding of how the game worked, and was quite bad at it. I now understand this was due to the fact that one of the game’s toughest difficulty spikes comes in the opening hours. But as an adult? With my developed adult prefrontal cortex and 15+ additional years of gaming experience? It was only moderately difficult. I played and beat Sekiro for the first time this year (and I’m talking about goddamn Mega Man Legends right now instead, yes. I was given space this platform, and I get to choose how to waste it), so I was spurred on by my courage to play maybe difficult, maybe occasionally incomprehensible games with no guides or outside interference. And it felt good. Really good. There’s a lot of value in revisiting games from your childhood, I think (I played a Paper Mario randomizer this year, which was an incredibly gratifying experience since Paper Mario is a game which I have beaten many times, most of which were in my childhood—listen, I’m talking about Mega Man Legends right now, don’t distract me). Sometimes it’s just nice to have a reminder of how far you’ve come, even if the games back then had controls that were way more shit than you remembered.

Oh yeah.

MORE GAMES SHOULD HAVE SHIT CONTROLS

This is a sensationalized paragraph header, but it’s how I feel. When Mirror’s Edge came out, my friends all hated it because of how complicated the parkour controls were. (“Why should I have to press like 7 buttons to wall jump?” they bemoaned. “I can climb a wall with the control stick in Assassin’s Creed.” Vile.) Sometimes things are good because they are difficult. Mega Man Legends controls like a tank. Turning is slow and intentional. You can’t shoot and run backwards at the same time. This is fantastic, because Legends doesn’t expect you to have lighting reflexes. The controls are consistent, learnable, and suited for the task: semi-tactical action RPG combat. And it expects you to learn them. You will learn how to control Mega Man’s blocky ass or you will perish. Speaking of blocky asses…

PS1 GAMES LOOK GOOD AS HELL

I love the polygons, the jaggies, the weirdly stitched-together jittery textures. Legends benefits from also having an incredible stylized aesthetic that benefits from flat shading, but I’ve always found PS1—and N64—graphical jankiness to be incredibly charming; see Pseudoregalia, Crow Country, Cavern of Dreams, and whatever Bloodborne Kart is called now. People crave the polygons.

After talking to several people, I’ve determined that I’m mostly Wrong about this, and most people do not crave the polygons of decades past. I would encourage you to contact me via email if you wish to argue this point with me, but I’ve been told you must instead [reads from notecard] “inscribe your message on a leaf and float it down the nearest river.” I have been assured this will work.2 I don’t know, it’s not my website, I don’t make the rules.

BIG STUDIOS SHOULD MAKE INDIE GAMES

Earlier this year, I also played the entire Sly Cooper trilogy. I will not be discussing them here. Send me a leaf, nerd. I will mention, notably, that those games all released within three years of each other. I will emphasize: the third Sly game came out almost exactly three years after the first Sly game. One of my favorite series, the “Tales of” series, released 10 games between 2000 and 2010. They’ve released two games in the last 10 years. Persona 3 released in 2006, Persona 4 in 2008, and there has only been one mainline Persona game in the 17 years since then.

Look, I’m talking out of my ass here. I don’t have “data” or “research,” but how many Mega Man Legends do you think a AAA studio could pump out in five years? How much can that budget and staff accomplish in a year? They could probably whip that shit out every six months (they shouldn’t). If big studios stopped worrying about the graphical fidelity of their characters’ eyebrow textures or whatever, maybe we could have a lot more cool games. Or at least more flawed, interesting games, like we did between 1990–2005.

THIS ISN’T A REVIEW

I dunno what this is. I’ve lost the thread, now. Should you play Mega Man Legends? I dunno. Probably not, honestly. It doesn’t feel “good to play” and it doesn’t always “tell you things” and the boss battles are “mostly bad.” I loved it. It’s goofy and colorful and there’s a vitality to the way these characters act that I simply don’t see very often. I played The Hundred Line: Last Defense Academy for 200 hours this year (send me a fucking leaf, I dare you) and I liked it a lot, and find it impossible to recommend to basically anybody.

WHAT IS THE POINT OF ALL THIS, THEN?

I guess, go find your joy. I can’t tell you what games you’ll like. I can only tell you my own lived experiences. Try something weird. Get frustrated. Dust off something you haven’t touched in two decades. Stick with it. It might change you in ways you didn’t expect. Play some of the other games recommended on here, really. You never know what unassuming game (or blog post) will radicalize your thoughts about the entire medium.

A DAD’S GAMING DUO

Contributor: Matthew Quann

Tis’ a shame that I write to you with the pads of my fingers pressed against these square keyboard tiles when my thumbs saw the greatest toughening. Indeed, dear reader, your humble correspondent from the vomit, tantrum, and perpetually disordered lands of parenthood is here with a missive about precious moments stolen away by sword swipes delivered at the push of a button. I racked up a respectable 110 hours behind the controller this year, which is perhaps a paltry sum compared to the years when I’d count those hours over a few months. Nonetheless, it was a banner year for me playing two games that left me entirely in awe and appreciation of modern gaming.

Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 is, I am pleased to report, everything it was chalked up to be and more. I lamented the watering down of Final Fantasy through its fifteenth instalment last year, but imagine my absolute pleasure at discovering that turn-based RPGs could still be cooked up with some goddamned SPICE. This game looks and plays fantastic as it ventures across a dreamlike landscape of seeming endless imagination. The retro elements, in particular the overworld map traversal, produced a regular burst of dopamine to my brain’s nostalgia centres while the combat took a classic formula and dialled in new elements one after another. Each character having their own quirk in gameplay made the construction of each party of three to be a strategic and rhythm based decision that made for an incredibly explosive feeling of triumph when a bout went exactly as planned.

If the game had simply been that, I’d have been satisfied. Imagine my continual delight at the mature, nuanced, and well-paced storyline. Each of the characters here is burned into my mind and I could appreciate their unique points of view over the some 30-hours I spent with them. There’s a decision at the end of Act I of the game that many studious would be too precious to ever consider, while Sandfall boldly strides into storytelling avenues that challenge the player and story that’s come before. I’ve had the experience of subversion of expectations frequently in literature, but seldom does it happen in video games. More of this sort of thing and less open world slop, please!

Speaking of open worlds, I continued my retro-futuristic gaming streak with the long anticipated arrival of Hollow Knight: Silksong, tapping into the Metroidvania hole that’s sat with me over the last few years. From its opening moments to the closing of Act III, Silksong is an utter marvel. The beautiful art style coupled with controller-smashing-inducing combat was a welcome return to Team Cherry’s oeuvre of bug kingdoms. What’s more, Hornet is an entirely different beast than the slow, but hard hitting knight of the first game. In Silksong you move fast, but it takes far longer to beat down the enemies’ carefully crafted attack patterns. Indeed, the loop of repeating boss attempts is an exercise in attention and simply the best rendition of this play style that I’ve experienced. Some of the runbacks are long, yes, but git gud.

Story in Silksong is brought to you by the lively cast of bugs that populate Pharloom. Each of these adorable or utterly disgusting creatures gives you a glimpse behind the curtain of the larger story at play. Sure, a Youtube video can explain the intricacies of the story, but playing Silksong is the only way to FEEL the story. Also, I’m here to be a stan of Hornet as the better of the series two protagonists. She’s honourable, relentless, and suffers no fools. As I struggled against the most vicious of beasts at intense speed, Hornet’s steadfast determination and gumption was a steady reminder that persistence in the face of incredible adversity does yield eventual victory. That I coupled my play through of this game with my first foray into Berserk was a study in facing extreme adversity.

My journey in Pharloom was joined by the latest addition to the family, who’s been a challenging baby even for experienced parents. Long evening and night hours were spent with a writhing baby in arms as I hacked, clawed, and platformed my way through the Citadel and into the pits of the Abyss. It’s a strange a way as any to bond with a young potato and I believe is noteworthy for nothing else than adding an extra layer of difficulty to what is already one of the most punishing games I’ve ever played. I invite anyone to enjoy the game with the near constant threat of clothing-soaking vomit lurking around every corner.

So, yeah, a pretty notable year for gaming in my books. Looking to 2026 I’m feeling the gravitational pull of Hades II, but may put that off in favour of something that won’t put calluses on my thumb pads. I’ve read and watched some things about Dispatch and think that’s where I’m likely to go next. Disco Elysium is also on the perpetual docket, but some shorter games may suit me well and bring up my numbers in the new year.

THE GEAR AND THE SPIRAL

Contributor: Stephen Friedrich

I’ve been thinking a lot about game narrative structures lately, especially after a run of recent (and highly-acclaimed) game narratives left me cold. It isn’t even necessarily the quality of the writing that I take issue with much of the time—though it often leaves much to be desired—so much as that the structure of many game narratives themselves don’t actually lend themselves well to what makes games narratively compelling to me. Spurred on by this vague sense of frustration, I decided I’d take this space to try and figure out where that feeling comes from, lay out a couple alternative structures to conventional three-act storytelling, and in so doing hopefully show how gameplay systems themselves can be narrative tools.

NARRATIVE IS EVERYWHERE

I find there’s often a conflation of game narrative with games writing in a way that obscures what games in particular can do, as well as limiting our understanding of what games could be. Many genres do not lend themselves to large amounts of text. Nor is that amount of text always desirable—in fact, I’d argue that most games writing, especially dialogue, could and should be shortened significantly. What I’m interested in is games narrative, which I am somewhat idiosyncratically defining here as the sum of a game’s written text, the semiotics of its visual elements, and what the game designer Brian Upton calls the “Game as Understood”—our mental model of how a game’s systems and world operate. This implies two things that I’ll build on below. First, narrative is internal to the player as much or more than it is conveyed by a designer. Second, narrative is everywhere, infused into nearly every design decision from programming to art.

Cards on the table: this is a deliberately provocative and maximalist position and one that I don’t see a lot of people share. On the one hand, it is incredibly broad—you might easily say that what I am describing is just “game design” tout court. On the other hand, game production is an industrial process, and industrial processes lend themselves to Fordism, dividing production into discrete and non-overlapping roles. This is useful, especially at scale—you cannot make Assassin’s Creed: Shadows or even Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 with a team composed entirely of artist/writer/programmer/producer Wunderkinder.

These are both fair objections and I’ll bite both bullets for the sake of brevity here. That said, I think finding ways wherever possible to break out of these silos is essential for the medium as a whole and key to unlocking games’ narrative potential.

A good first step in breaking down these silos is to look at gameplay structures in narrative terms and vice versa, thinking of them not as gameplay loops and narrative arcs but as unified, holistic structures. To illustrate what I mean, here are two games and their underlying structures that I’ve been playing this past year—what I call the Gear structure, represented by Master of Command and the Spiral structure, represented by Frostpunk 2.

THE GEAR: IT’S THE NARRATIVE YOU DON’T WRITE

Due to a combination of the winter break, a bout of illness that confined me to my apartment, and being a card-carrying History Sicko, Master of Command has consumed my life. It is a roguelike army management game, Empire: Total War meets Monster Train, set during the Seven Years’ War (or French and Indian War, to my fellow Americans). You command an army of Prussian, French, British, Habsburg, Russian, or Holy Roman soldiers through three phases of the war, equipping each regiment with weapons, supplies, and pocket Bibles. 3D, Total War-style battles are punctuated by a procedurally-generated overworld with choose-your-own-adventure random encounters and the micromanagement of your regiments, their officers, and your supplies of manpower, ammunition, money, and supplies.

You might have identified some obvious narrative structures in the description above. The game is divided into escalating acts, contains light narrative flavour through its choose-your-own-adventure snippets, and the five base army types each relate to the game’s systems differently. These are all true, all narrative systems in their own right, and all not what I mean to highlight.

The real narrative juice of Master of Command isn’t just in these elements, but in the things it leaves space for the player to do—that is, invest emotionally in these little pixelated soldiers. You can rename each and every regiment, brigade, and officer in your army. You can customize each of their uniforms, give each a distinct set of strengths and weaknesses, organize them into neat little rows like the adorable toy soldiers they are. What elevates this from merely fluff to a major narrative element is that you really need to do this. In the heat of battle, especially at higher difficulties, it becomes incredibly valuable to know at a glance which of your light infantry has the cheveaux-frises they need to deter a cavalry charge or recognize which of your artillery batteries can turn their cannons into giant shotguns filled with canister shot.

I did this when faced with the extremely varied Habsburg army, drawn from all corners of a multi-ethnic Central European empire. My light infantry, be they Austrians or Croats, wore green caps, their jacket facings indicating if they could stand up in melee if it came to that. My heavy infantry were red, with facings indicating their relative skill at range. Each regiment developed its own history, its own narrative of the scrapes and skirmishes it endured over the war. When my elite Grenzer Sharpshooters were shattered by enemy cavalry, it hurt not just because I would need to spend valuable Reservists bringing them back up to strength, but because they had been with me from the very beginning, had seen off so many enemy regiments many times their number and now were fleeing for their lives because of my inattention.

I have to stress that none of this narrative is written, but all of it is intended. It flowed naturally from my engagement with the game’s systems. The game gave me both an opportunity to invest emotionally in its systems, but also a reason to do so. I tend to bounce off of games that are complete sandboxes for the sake of it—I don’t care if I can do something, I want to know why I’d want to. For a game to evoke this feeling, it has to both leave gaps but also provide strong mechanical hooks in a pattern resembling the alternating tooth-gap pattern in a gear, thus my name for this structure. Systems-heavy games like strategy games lend themselves well to this, but it’s equally applicable to management simulations, city builders, RPGs, and more.

THE SPIRAL: NICE JOB BREAKING IT, HERO

The other structure I want to sketch out here is The Spiral, best illustrated by 11bit’s survival/city-builder Frostpunk 2. I adore both this game and its predecessor and heartily recommend both, but for the unfamiliar, Frostpunk is set in an alternate 1886 in which the world has been plunged into an eternal winter. As the dictatorial Captain of an expedition to the far North (because one may as well go where the local fauna are adapted to the cold, anyway), you manage your colony through a desperate struggle for survival, making difficult decisions and moral compromises for the sake of getting through another bitter storm. Sure, you don’t want to impose child labour, but you do really need a few extra bodies in that coal mine to keep the Generator running and the kids, as they say, do yearn for the mines.

Frostpunk 2 elaborates on this, taking place thirty years later. The city of New London has grown, the Captain is dead, and mere survival isn’t good enough anymore. You take on the role of the city’s Steward, a Prime Minister of sorts, answerable to a Council of emerging political factions. Any major changes to how New London does things has to go through them, which means cutting deals and making promises in exchange for votes. These, in turn, become short-term objectives. You may not actually need that new Moss-Filtration Tower, but promising to build it may be the only way the survivalist Frostlanders will go along with your plan for mandatory schooling (welcome back from the mines, kids! Here’s thirty years of accumulated algebra homework).

In contrast to the first game’s relative linearity, Frostpunk 2 exhibits what I call a narrative Spiral. You have a set of overarching constraints—your people need food, housing, raw materials, heat, and even consumer goods, the ungrateful rabble—and every single action you take to address these constraints advances the story in some way. And I do mean every action. Build a new Housing District? One of the city’s factions immediately moves in, altering the Council’s balance of power. Want to research a new technology? You’ll need to decide on how that specific tech will be integrated into New Londoner society, which, you guessed it, will alter the balance of power.

There are multiple equilibria here, none of them stable. You can throw your weight entirely behind one of the game’s factions, all of which have been tailored to be “right in some ways, wrong in others.” Of course, all of the people who don’t see the world the same way will progressively radicalize, taking their opposition out of the Council chamber and into the streets, where even a minority can bring the entire city to a halt. Of course, you could try to maintain a balance, neither pleasing nor displeasing any one side. This results in a patchwork city, opening some new synergies but locking off others, not to mention a Council that stays so divided that wheeling and dealing becomes constant and mandatory.

Gameplay and written narrative are more clearly delineated in the Spiral relative to the Gear, and indeed there is vastly more text in Frostpunk 2 than Master of Command, but what distinguishes it as a ludic narrative form is the runaway-train feeling of action and reaction that ties all of its elements together. My favourite TTRPG system, John Harper’s Blades in the Dark, excels at this—because of how its dice are used, every single thing the player does will advance the story somehow, in both success and failure.

Like Master of Command’s Gear structure, the Spiral structure of Frostpunk 2 demands the player co-write the narrative with the designers as they go along. The narrative is not incidental, it is essential to, and coterminous with, the gameplay. To play Frostpunk 2 is to lead New London is to roleplay your Steward, all at once.

What I hope this (overlong, sorry [redacted]3) article demonstrates is that game narrative and game design are not separable concepts. Games can constitute a narrative form all their own, breaking out of traditional arc structure and into something altogether unique. I’m under no illusions that this will ever be the dominant paradigm—there’s just too much money and institutional momentum tied into existing ways of doing things—but I hope it resonates with both players and designers and that we can appreciate these beautiful intersections where we can find them.

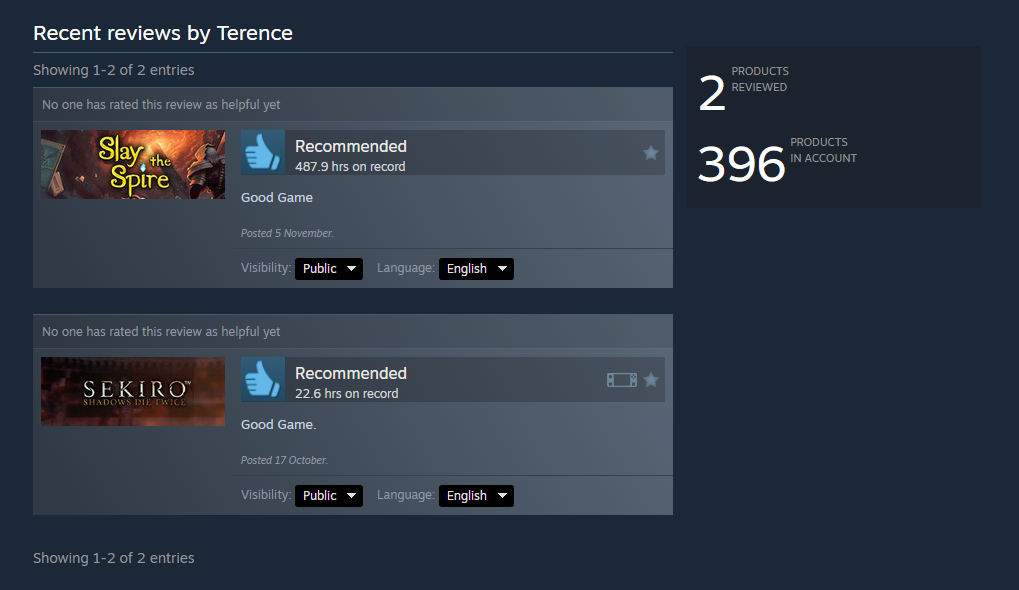

RECENT REVIEWS

Contributor: Terence

My thanks again to everyone who contributed, and to you as well, if you are still reading, here, now, as the light is dimming. This is the second year that I have done this, which is probably enough to call it an “annual” post. If not, well, three’s company and four for a boy, five for the computer, and six for toys. See you all next year, god-willing.

Footnotes

I’ve heard some people didn’t even like Blue Prince that much.↩︎

Editor’s note: It will.↩︎

Editor’s note: is ok :)↩︎