I can basically tell you the month that I started to care about parrying: it was June of 2019, when I played Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance for the first time. It was the only modern Metal Gear game that I’d never played1 and although I was not especially optimistic about the game—I thought it seemed just as silly as everyone else did for the game’s first few years after release—I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to play a Metal Gear game developed by the inimitable PlatinumGames.2 I even plugged in my PS3 specifically to play it, as the game had never come to modern consoles. For those unaware, Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance has very little in common with the Metal Gear franchise. Although you play as Raiden, the protagonist for (most of) Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty, and although the game references the events and mythology of the Metal Gear universe, the similarities essentially end there. Instead, Revengeance puts you in the role of a cyber-ninja who uses a “high-frequency blade” to slash other cyborgs and robots to shreds, ideally in such a way as to consume their Juices afterwards and restore your health and mana. The game has more in common with Devil May Cry or Bayonetta than it does with any other Metal Gear title, though it does a tolerable job of imitiating the bizarre tonal cocktails of the mainline Metal Gear entries.

Other than its repeated use of nu-metal needle drops and having a right-wing American senator who says “Make America Great Again!” for a villain, what’s unique about Revengeance is that it has no dodge button and no (traditional) block button. The game prioritizes attack, no doubt—your attacks are lightning fast and if you land enough of them you can interrupt an enemy’s attack—but defence is still a necessity if you want to succeed in the game. Getting hit by even basic attacks can be devastating and can lead to getting stun-locked and gang-beaten by the hordes of cyber-goons constantly chasing you. Happily, the game provides (and strongly recommends) a very simple solution: parrying. Parrying is done by pressing the attack button and flicking the control stick towards the enemy immediately before their attack will land. Less precise inputs will result in blocking the attack, mitigating all damage and potentially giving you a chance to turn on the offensive and take out the enemy. Perfectly-timed parries will block the attack and automatically trigger a counter-attack, which can then be chained into any number of impressive acrobatic feats.

Explaining this parry system in such verbose detail will strike many of you as trite and unnecessary, I am certain. However, these details are crucial to understanding how Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance convinced me to start caring about parrying. The game provides no realistic defence strategy other than parrying. There is no traditional block button and there is no dodge button. If you wish to play the game on the default difficulty (or above) without dying constantly, you have no choice but to learn to parry. Thankfully, learning this defence strategy does not impede the flow or speed of the player’s offence. To the contrary, it is the metronome that paces your attacks. It provides the commas between strings of strikes. It helps the player to feel the pattern and flow of combat, rather than arhythmically mashing on the attack button. This process is expedited by using the same button for attacking as for parrying—the only change in input is the addition of a directional input. In this way, Revengeance becomes a rhythm game in diguise, obscuring this nature by converting the lanes and arrows of a traditional rhythm game into something more visually-complex but phenomenologically very similar. At its best, this system encourages the player to be intentional and deliberate while also lulling them into a state of flow, a semi-conscious unmediated3 experience more akin to playing a well-practiced instrument than an action-packed videogame.

So why did it take me 20 years to start caring about parrying when it’s a mechanic that is nearly-ubiquitous in action games? Well, in short: I think parrying in videogames is often quite bad. I think that the science and art of designing a good parry are very delicate; there are aspects of it that can be described easily (e.g, the parry should work when you press the button) but because it’s such a gestalt of so many different things, it can be very difficult to explain in concrete terms (beyond something like “good parry feel good”, as illustrated in the introductory image). Parrying is about feel, but this comprises so many different aspects: weight, speed, timing, animation, and sound, each of which applies to two different entities (both the player character and the enemy). Put this way, it seems shocking that any game has been able to make it feel good and natural in the midst of all of the other complexities of combat.

However, in spite of the intimidating nature of this topic, we have already begun our investigation by identifying one good example of parrying (Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance), what distinguishes it from other games, and why its parrying feels good. We can continue this descriptive research by examining other prominent examples of parrying in videogames, identifying how and why they succeed or fail. We can also orient these discussions around the themes already identified above: rhythm, flow, and feeling.

DARK SOULS

“Hmm, well, there’s nothing forlorn about you.”

At the risk of starting things off on a negative note, it might be most fruitful to first discuss a very prominent example of (what I consider to be) extremely bad parrying. For all of their many, many strengths, the three Dark Souls games (and their shameful bastard sister, Demon’s Souls, and perfect goddess cousin, Elden Ring) are very illustrative examples of how not to implement parrying. It can be sort of difficult to explain how parrying works in these games, because most players simply do not try it. Those who do likely abandon the effort before too long, writing it off as another one of FromSoft’s needlessly-obtuse and obscuritanist systems. Those who haven’t played the games might not even understand how it’s possible that the system is implemented this way at all.

In Dark Souls, your main forms of damage mitigation are blocking and dodging. Most players use some combination of the two4 and they work in essentially the way you’d expect: blocking reduces damage but consumes stamina; precise dodging avoids damage altogether. Your third option is parrying. If you successfully parry in Dark Souls, you mitigate all damage and stun your opponent, allowing you to riposte them for a huge amount of damage.5 Thus, the reward for parrying is very high—but so is the risk. Parrying doesn’t use the block button and so it is mutually exclusive from blocking. A missed parry may mitigate some damage, but it may also mitigate no damage, leading to you taking the full brunt of the attack. You may also be stun-locked by the attack, and given how easy it is to die in even typical encounters in Dark Souls, it is no exaggeration to say that this missed parry could lead to an untimely death. Thus, parrying is a risky maneuver, even in its idealized form.

Essentially every weapon and shield can be used to parry,6 though only a handful of them are feasible for doing so. Every weapon and shield has a secret stat indicating how effective it is at parrying (i.e., the number of frames in which it can successfully land a parry). If a piece of equipment does not specifically say in its item description that it is good at parrying, then it is effectively impossible (beyond guessing) to know whether it will be effective. This means that you, the player, are essentially forced to consult google if you wish to have any hope of parrying reliably. Although I am tolerant of a certain level of “you should just google this” in FromSoft titles, basic combat mechanics should never require these sorts of external aids. But, okay, sure, fine, you can google which shield or offhand weapon to use as your parrying tool. Now you should be fine, right? Well, it turns out only some attacks are parryable. Which ones? No one’s quite sure. It’s not consistent within the game and there’s nothing about the attacks or the enemies themselves that indicate whether an attack can be parried. You just have to try it and see if it works or if you get hit. Just make sure you get the timing right—otherwise you won’t know whether the attack can’t be parried or if the timing was just off. Oh, and I should also mention that every parryable attack has a different parry timing—sometimes you want to parry just before the attack, sometimes you want to parry right when the attack lands, sometimes it even feels like you have to parry a split-second after the attack lands. Each of your parrying tools has a different speed too, so it’s never as simple as just pressing the parry button when the attack would land. No, you have to press the parry button in advance of the attack, based on both how fast your parrying tool is and on the individual parry window for that attack.

So, to recap: parrying is based on a hidden stat, can also only be used on some attacks, and its timing differs between equipment. These attacks have different parry windows and the game does not indicate to you whether an attack wasn’t parryable or whether you just failed to parry it adequately. Missing a parry can sometimes be devastating—up to and including death—but landing one just leads to a satisfying noise and reasonably-strong attack.

This is, of course, extremely bad parry design. The system is obtuse, risky, and often feels “random.” Moreover, the mishmash implemention of different parry windows for different equipment, attacks, and enemies impedes the flow of battle, interrupting the rhythm that might otherwise be achieved by just committing to the in-out dodge-dodge-attack paradiddle of combat. It is sort of unbelievable that they have kept this system for so many games (Demon’s Souls, Dark Souls 1–3, Elden Ring). In my first playthroughs of Dark Souls and Dark Souls 3, I did not parry a single time. For both games, I only learned to parry during my “Soul Level 1” runs of the games, in which the player beats the entire game without leveling up past level 1. In both cases, I only learned to parry when it became essentially-necessary to beat a given boss, such as Gwyn in Dark Souls or (Champion Gundyr in Dark Souls 3).7 When sharing the video of my attempt on Champion Gundyr with series veterans, I even received the comment multiple times that “[they] didn’t even know you could parry [that specific attack]!” This is because the system is so obtuse and opaque and hostile to the player—and not in the good ways—that even series regulars aren’t totally clear on how it works. Broadly speaking, the system has gotten better with each iteration, but given that they have already produced such excellent parrying, it is unclear to me why they would keep returning to this particular type. So, let’s talk about some better parrying.

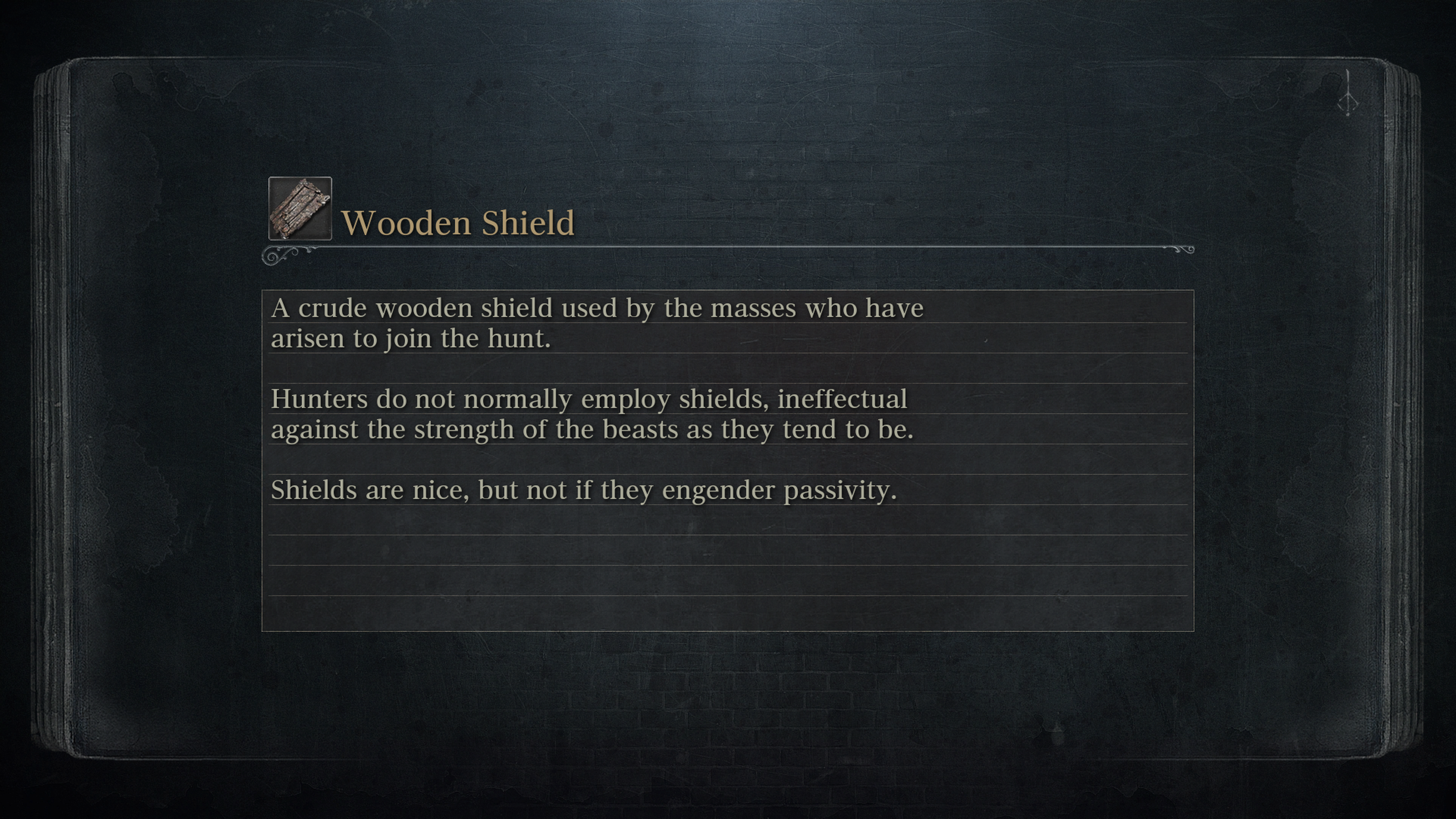

BLOODBORNE

“You will hunt beasts and I will be here for you, to embolden your sickly spirits.”

We’ve still got a ways to go so let’s cut to the chase: Bloodborne is Dark Souls but with fast combat and without blocking. Shields engender passivity and so, in order to maximize aggression and flow, they’ve been removed from the Bloodborne equation entirely. When you do take damage, you can recover some of that health by damaging the enemy soon afterwards, which is known as the rally system. This leaves you with your weapon, a backstep, and a gun in your off-hand that can be used to parry. Guns differ in speed, damage, and bullet consumption, but generally the faster and weaker guns are better for parrying. If you’re using a fast gun, pressing L2 just a split second (specifically, about 10 frames) before the enemy’s attack lands will successfully parry them. This plays a big satisfying gong noise, stuns the enemy, and allows you to land a visceral attack for massive damage.

Based on this description alone, the parrying in Bloodborne may sound similiar to that of Dark Souls, but there are a few key differences. The main difference is: you press the parry button approximately when an attack is going to land (as opposed to pressing the button well-in-advance of the attack). Different attacks sometimes have slightly different parry timings but, broadly speaking, you press the parry button when you are going to be hit by an attack. This is a subtle difference—likely one that comprises only a few frames or so—but it has a massive impact on the flow of combat. Instead of interrupting the current of combat to coarsely insert a slow and awkward parry, the parries are themselves seamlessly woven into rhythm and flow. Watch the enemy and feel the speed and cadence of attack animations; dodge, dodge, parry, attack. The rally system bolsters this system even further by encouraging you to maintain the flow and pace of combat even if you get hit; instead of dodging out of the fray to regroup, renew the assault, channel the rhythm, restore your health, continue the dance. Bloodborne is much faster than the Dark Souls games (especially those released before Dark Souls 3) but its parries feel much more natural and much easier to land, despite the higher demands on your reaction time. This is because of how tight and responsive each of your actions (typically) are, which is especially demonstrated in fights against other Hunters, like Lady Maria of the Astral Clocktower.

One other subtle change introduced by Bloodborne that has an outsized effect on the experience of combat is the relative nerfing of dodging, when compared to other FromSoft titles. Players in Dark Souls (etc.) determine how fast and effective their dodges are using the equip weight system. The heavier one’s equipment (which usually corresponds to more effective armour), the less effective one’s dodge becomes; specifically, it becomes slower, it travels less distance, and it provides fewer frames of invincibility (aka “i-frames”). Bloodborne dispenses of this system entirely8 and gives all players the same “fucking useless” dodge. Although I would strongly disagree with this distinguished GameFAQs poster, they are certainly correct that the dodge is much less effective and reliable than in other FromSoft games.9 Players must be much more careful and exactly when and where they dodge, and they must also learn to recognize when an attack should be parried instead of dodged. Both parries and dodges require precise timing, far more precise than the generous dodge rolls of other FromSoft games.

The weakened dodge, when combined with the increased speed and aggression of Bloodborne, can make for a frustrating and hostile experience, even (or especially) for veterans of other FromSoft games. However, this is also what makes Bloodborne’s combat so unique and compelling. The removal of blocking and the weakening of dodges forces players to focus more on rhythm and timing than they ever would have otherwise; it forces the player to either learn to dance or to suffer defeat after miserable defeat in Yharnam. It conditions the player to see each enemy (or mob of enemies) as a different dance partner, each requiring a different style of dance with unique tempos and time signatures and rhythms. Here is where we begin to see the true contribution of a good parry system: it locks the player in step with their opponent in a way that blocking (and, to some extent, dodging) never could.

Bloodborne’s parry system, wonderful as it is, yet retains some flaws of the other Souls games, however. As mentioned previously, enemy’s attacks do seem to vary unsystematically (if only marginally) in their parry timings. Furthermore, although most enemies and attacks can be parried, not all of them can be, and the game does not communicate which is which to the player. Failure to parry may be the result of an imperfect execution or it might just be impossible; this ambiguity prevents players from ever being able to fully commit to the parrying system. Thankfully, From Software made one more game that iterates on the parrying system that they’d nearly perfected in Bloodborne.

SEKIRO: SHADOWS DIE TWICE

“May you live on and embrace what it means to be human.”

Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice is a game in which players take the role of a one-armed shinobi tasked with protecting the Divine Heir of a mystic bloodline. As Wolf, you rely on your sword and a repertoire of shinobi tools to defeat the various samurai, bandits, giant snakes, and malevolent spirits that inhabit his world.10 The game is beautiful, quiet, and a little bit haunting. For many, it is also the hardest game released by From Software.11 It is, to quote a Reddit user,12 the only FromSoft game that “does kinda demand perfection.” The average FromSoft player finds Sekiro particularly difficult for a few reasons. First, the leveling system has been heavily simplified, and there is no traditional means of grinding levels to increase your health, attack, or other character attributes. Because the developers know that all players will be facing each boss on approximately-equal footing, every encounter has been meticulously titrated for a specific level of difficulty for a specific character build.

Second, Sekiro essentially requires players to learn how to parry, and to learn how to parry well. Although someone sufficiently motivated to have a miserable time with the game could avoid ever parrying by cheesing every encounter (i.e., finding a “cheap” way to beat it), most encounters in the game—especially boss fights—revolve around parrying your opponent. Like in Bloodborne, your dodge is not as effective as you might expect; unlike in Bloodborne, you do have the option of blocking. But blocked attacks deplete your “posture”, and if your posture runs out, you will be stunned and become vulnerable to a devastating critical attack. However, as above, so below; you can deplete your opponent’s posture by parrying their attacks, and most fights will be decided by doing so and landing the resultant critical attack. In this way, the best encounters in Sekiro feel like a delicate dance on the edge of a blade; a gently-devastating competition between two equals that will be lost if your mind is unquiet or your heart is unstill. Thus and so, we have identified the fundamental building blocks of Sekiro: careful defence, precise offence, steeled nerves, a tranquil mind.

Crucially, Sekiro develops upon its predecessors’ parrying systems in a few key ways. One such is that parrying and blocking are mapped to the same button; perfectly-timed button presses result in a parry, whereas ill-timed button presses result in a block (or in neither, if your timing was especially bad). The most important change, however, is that parrying happens exactly when you press the parrying button and you are expected to parry an attack the moment that it lands. In this way, Sekiro has perfected the rhythm-game-as-combat format intimated by Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance. Parrying works the way you think it should work and it feels amazing. The game’s visuals, sounds, and timing all combine to produce a parry that looks and feels incredible, all while being legible on a scale of literal milliseconds.13

Another critical change is that nearly every attack is parryable. The attacks that are not parryable are clearly indicated as such with a bright symbol and a loud noise preceding them. This keeps combat diverse and engaging, forcing the player to use different strategies to handle particularly strong attacks. One such strategy is a move unique to Sekiro, a sort of alternative parry known as the Mikiri Counter.14 Although you can parry thrust attacks if your timing is perfect, they cannot be blocked, and so failed parries will result in taking full damage. Instead, you can Mikiri Counter thrust attacks, stomping on the enemy’s weapon and inflicting a large amount of posture damage.15 In place of the parry/block button, the Mikiri Counter uses the dodge button, and has a much more generous timing window than parries and so is relatively easy to pull off. It also happens to be one of the best feeling moves in any action game. You stomp on the enemy’s weapon, a burst of wind emits from the blade, and a single deep drum beat resounds. Seriously, it feels incredible. It gets to the point where you’re excited anytime you see an enemy with a thrusting weapon.

These changes, among a handful of others, result in a parrying system that approaches perfection. However, they come with some concomitant adjustments in expectations of the player. Namely: the player will have to learn how to parry precisely and reliably. Those who refuse to adapt to these novel mores will likely find the game cruel, strange, and frustrating. Learning to dance is incredibly difficult even with an excellent teacher—and I do think that Sekiro is one of the best—but is effectively impossible if you refuse to heed her wisdom. And even for someone with a willing spirit and an eager heart, there is no denying that Sekiro is hard. Players are tasked not just with learning to develop a sense of rhythm and flow, but to do so under extreme threat. Mistakes will be punished and the careless student will progress slowly and seldom, if at all. Thus, they must also learn to be calm, still, and fleet-of-foot. Anticipating your enemy’s movements and attacks is difficult enough as it is, but is made all the more so by an anxious heart. A frantic mind will reel in response to a mistake, failing to recover its balance or rhythm and producing a gait that is heavy and awkward. It is only by quieting and disciplining these faculties that one can begin to hear the gentle rhythms that reside in and underneath everything else.

It is these expecations that are at the heart of what makes Sekiro such a difficult game, but they are both the cause and result of the game’s unique quality. Only a game approaching perfection16 in this way can have such rigid and extreme expectations of the player. Only by meeting such rigid and extreme expectations can Sekiro produce such a singularly-satisfying combat experience.

Despite what the preceding text might imply, I am sympathetic to the difficulties of developing a parrying system. Speaking as someone who is neither game designer, programmer, artist, or sound designer, I cannot imagine how difficult it must be to bring all of those elements into the synchroncity necessary to produce a parry that feels compelling and organic. Setting that challenge aside, however, there do seem to be some high-level themes that have emerged from our investigation. Good parrying rewards play that is aggressive, but deliberate and intentional; thoughtful, but not passive. It incentivizes active and agentic engagement in the combat, especially when compared with, for example, turtling up and blocking every attack until there is a wide open window for you to punish. It is typically best-realized when dodging isn’t the de facto defensive maneuver, and perhaps especially when dodging is a poor one.

When parrying is good, combat feels like a dance or a rhythm game. It provides the player with a level of immersion seldom found elsewhere, achieved by ushering them into a psychological state of flow that feels unmediated by conscious thought or mechanical medium. Once you master it, you will feel it sway about your mind and you will learn to walk a little more gently.

Some final errant thoughts:

- I had originally intended to discuss Lies of P in this post, but given how long it already was, it didn’t seem necessary to elaborate further on my previous comments. Also, I had already decided on this heading format and I couldn’t think of a good quote from Lies of P to use in it.17

- The parrying in God of War (2018) and God of War: Ragnarok is also pretty good. I played the prior before Metal Gear Rising and the latter afterwards, so naturally I parried very little in God of War (2018) but did an extremely parry-focused playthrough of God of War: Ragnarok. It’s funny to see how the intervening years conditioned me to play Ragnarok so differently from how I played its predecessor.

- It should probably be noted that I am a massive fan of rhythm games and that that is inextricable from how I interpret parrying. If you’re not, then uhhh. I’m sorry, I guess. Though you probably don’t care about parrying anyway.

- The moment I came to grasp most of the principles described herein was when I beat O’Rin of the Water on my first attempt, without having any previous knowledge or awareness about the fight. She is considered to be a relatively difficult boss—an extremely difficult one, for some—but I found that I understood her implicitly and, to put it bluntly, parried the everloving shit out of her.

- I previously threatened to discuss parrying for about 5000 words. This estimate turned out to be remarkably close (somewhere in the realm of 5400 words, by my count). It was mostly outlined and written in April but I was waylaid by card games and other things of profound importance. I am pleased to have completed it.

Footnotes

While editing this, I remembered Metal Gear Survive. Doesn’t count.↩︎

For those curious, Platinum is responsible for Nier Automata (one of my favourite games), Bayonetta, Vanquish, Astral Chain, and (in a certain sense) Okami. They are known for producing combat that is extremely fast, tight, rewarding, and ultimately feels Extremely Good.↩︎

That is, an experience that feels like a direct connection between the player’s mind and the game, unmediated by things like controls, controller, or latency.↩︎

Though the most enlightened among us simply equip the Grass Crest Shield, two-hand our weapon, and exclusively rely on dodging for damage mitigation.↩︎

The parry also makes a pretty cool noise.↩︎

The pedant may note here that in Dark Souls 3, many weapons and shields actually cannot be used to parry, to which I say: that is correct but is immaterial to the broader point that I am making. However, I thank you for your immortal dedication to precision in this, as in all things.↩︎

These parries were also only realistically possible because I’d equipped the Caestus, the fist weapon dedicated to parrying that cannot do a traditional block. It has the fastest and most generous parry window in the game, but you still don’t know which attacks can or cannot be parried. Great, sounds good! Thanks guys!↩︎

Although I have never encountered explicit discussion about this particular issue, I would imagine that it is a controversial change among at least some segments of the fanbase. Though there are aspects of the equip weight system that I find interesting, I do find that it often causes more problems than it solves. For example: the majority of equipment you find over the course of a Dark Souls game will be so heavy as to be unusuable until the end of the game, when you’ve improved your equip weight stat sufficiently. Players who wish to play with the fastest roll are especially punished for this and are relegated to choosing between only a handful of very light armour sets. I am not opposed to the idea that players’ appearances and behaviours are constrained by their character’s stats and combat style—that’s part of what makes RPGs so compelling—but it just feels like this system ends up constraining nearly everyone in basically the same way, allowing very few players to experiment with different armour sets and appearances for much of the game. Bloodborne gets around this problem by getting rid of equip weight altogether, providing players with no shields or means of blocking, giving everyone the same dodge, and having only minor stat differences between armour sets. I personally did not lament the loss of the equipment weight system in Bloodborne, but I do think that these other changes were likely necessary in order to adjust for its absence.↩︎

Although I included the screenshot of that post’s title as just a bit of comedic evidence, the post itself is fairly illustrative of a player who “does not get it.” This is someone who likely relies heavily on blocking when playing FromSoft games and is compensating for its absence with an overreliance on a dodge of only mediocre efficacy, rather than learning to focus on the rhythm of combat and learning precisely when and where to dodge or parry.↩︎

On a related note, Sekiro happens to have my favourite swordplay of any videogame.↩︎

I knew this to be true in the same way that a bird knows how to build a nest for its young and a turtle knows to bury itself in pond mud for the winter months, conscious but unbreathing. That said, I thought I’d ratify my intuition with a quick google search, and I was not disappointed. Commenters from this post observed that Sekiro is the hardest FromSoft game “and it’s not even close” and that with other games “you can always turn around and do something else,” but with Sekiro, “you just gotta ‘git gud’ and die 1000x(twice).”↩︎

I will try not to make a habit of it.↩︎

For precision’s sake, I would prefer to say “centiseconds” here, but for some reason we have yet to adopt this term into common parlance. Answer my emails, Bureau International des Poids et Mesures.↩︎

mikiri counter i hardly know her thank you↩︎

A reminder: I refuse to directly embed looping gifs into these posts as I find them to be incredibly unpleasant and distracting when they cannot be paused.↩︎

(at least with regards to its parrying and combat)↩︎

Suffice to say, I think that the parrying in Lies of P is good, but not as good as it should be. It just never really quite feels right, and certainly does not reach the levels of Bloodborne or Sekiro. It is probably (and paradoxically) easier to master for people who aren’t treating it like a rhythm game. It is at least better than the Souls games by virtue of having a parry system that is not opaque or obscured by silly bullshit.↩︎