A friend recently pitched an interesting challenge to me: if you are giving a game a review score, never give it a 7. We all implicitly understand what this means: a 7 is a coward’s score.1 It sits perfectly on the fence between calling a game bad or good. It is a refusal to commit to either saying that a game has problems and ultimately fails or that a game is well-made and worth playing. If you take the idea of giving review scores to games seriously—and clearly, many people do—then it is a challenge worth considering. Maybe we should be extremely hesitant to ever sit on that fence, no matter how safe and alluring it seems. Maybe we should cover it in pigeon spikes.

I have no idea what the modal score in videogame reviews is. My gut tells me that it would be 7 or 7.5.2 So, if the preceding thoughts are correct, this would suggest that most critics are often quite cowardly. That possibility does not strike me as implausible and I suspect that most critics would feel similarly. But where do the other scores go? And what do these different scores represent? Is it possible that the common usage of a 7 is actually warranted? What follows is a consideration on these questions and others.

To begin, let us consider what we are measuring using videogame review scores. I will not wade into the dense aesthetics discourse of exactly what it means to evaluate a piece of art and will instead rely upon fairly simple and indisputable claims. First, review scores are meant to reflect some abstracted level of quality that is reasonably-accessible to a large number of people. For example, although I had an excellent time playing Fighters Destiny on the N64 with my brother, I do not believe that others would necessarily have the same experience playing that game, and so I would not assign it a particularly high score (because it is, in fact, a bad game). Second, review scores are a reflection of the critic’s individual taste and experience. Taste, skill, and personal experience are all crucial determinants of one’s perspective on a game, and some people are ultimately ill-qualified to evalute some games. I, for example, would probably assign a low review score to every Call of Duty game, as the game’s mechanics, tone, and style are of little interest to me. Note that although our first and second precept appear to be contradictory, they can exist in harmony: one’s perception of the “abstracted” level of quality of a game is determined in part by one’s individual taste, skill, and personal experience. Third, finally, and most contentiously, review scores are not perfectly comparative, but are generally so; perhaps not every “7/10 game” is ‘better’ than every “6/10 game”, but probably most “10/10 games” are ‘better’ than most “6/10 games.”3 This is a deeply complicated assertion, but it is probably true insofar as it is popularly-believed: most people would probably agree that games can be (at least sometimes) compared on quality, and that review scores are (at least sometimes) a useful way of doing so.

Having defined the general practice of assigning review scores, it should also be noted that many people simply do not believe it should be done. Many publications have, for one reason or another, eschewed the practice entirely. Some do not believe that it is a useful critical practice, either for the critic or for the audience; it belies the true experience of playing a game or it encourages audiences to obsess over the single numerical evaluation instead of the rich phenomenological evaluation provided in the accompanying review. Others do not believe that it even makes sense to attempt this practice, as the quality of a piece of art cannot be evaluated on a single unidimensional numerical scale. Many would also dispute the idea that games can be meaningfully compared on quality (i.e., “Nier: Automata is just as good as Persona 5”; or, “DOOM (2016) is better than the original DOOM”) and so they reject the idea of numerically evaluating games, a practice which clearly invites audiences to directly compare games on quality. Regardless of the validity of these arguments (and, for what it’s worth, I do believe that they have some validity), assigning review scores remains a popular practice that is clearly valued by audiences (rightly or wrongly). Furthermore—speaking personally—it’s fun. It is fun to give games scores, to argue about whether one game is better than another, to comb through Metacritic scores and debate the validity of this or that review score. The practice’s status as both popular and fun does not make it right, of course. It doesn’t make it harmless or theoretically-justified. But we cannot deny that the practice is popular and is widely-regarded as valuable, and so for those reasons, we can momentarily dispense of the discourse of whether review scores should even be assigned at all, that we might more deeply consider the practice as it is currently performed.

One notable pattern in review scores is the intense restriction of range. On a scale from 1 to 10, we seldom see scores lower than 6 (and even a 6 strikes me as highly uncommon). This means that the review score scale is, functionally, a scale from 6 to 10.4 In statistics, this is a problem referred to as a restriction of range. It can cause a whole host of problems in analyses but, for our purposes, we’re more concerned about what it indicates about our measurement. If five points of our ten-point scale are not being used, what does that indicate about the construct we are measuring and about our measurement? There are several possibilities. One is that there are genuinely no games that deserve a 2, for example, on a scale from 1 to 10. By way of analogy, consider height: although the range is technically from 0 to ∞, we know that the actual range is something more like 55cm to 275cm. Adult human height just doesn’t fall outside of that range. So, perhaps videogames abide by a similar principle: there just aren’t games that have “a 2” worth of quality on a scale from 1 to 10. But, of course, height is an absolute measure.5 A person with a height of 183cm is that height regardless of context or the height of others. Two people who have a height of exactly 183cm are the exact same height. Neither of these principles necessarily holds for videogame review scores, which seem much more like a relative measure: they are likely contingent on the context in which they emerge, they comprise a certain amount of uncertainty and noise, the same score for two different games doesn’t necessarily imply an identical measure of quality, etc. Thus, it does not seem to be necessarily true that games with less than “a 5” worth of quality simply do not exist in the way that adults shorter than 50cm do not exist. In other words, we are not necessarily forbidden from using the first five points on a scale from 1 to 10 (in the way that we are “forbidden” from using the heights of 0cm to 50cm for adults).

So, let us examine this possibility further. Perhaps it is the case that a game with “a 2” worth of quality could exist, but simply does not (or is exceedingly rare). One potential reason for this is that games with that level of quality do not make it through development (and publication) and then onto platforms for wide distribution. This is possible, though unlikely; a cursory glance through the dregs of the Steam store reveals all sorts of Weird Trash that clearly has not met any sort of stringent quality control. So, perhaps it is the case that most game critics do not bother to review games that seem as if they would be “a 2” worth of quality. This seems likely: most prominent critics work for websites that require clicks from as many people as possible, and largely-negative reviews of little-known games are unlikely to attract that sort of traffic.6 I also assume that critics are generally uninterested in publishing largely-negative reviews of little-known games, and for good reason: unless such games offer something particularly unique or novel, this does not seem like an especially valuable critical undertaking. Thus, we can reasonably conclude that games with “a 5 (or less)” worth of quality do exist, but are not receiving much critical attention. In other words, low and middling review scores exist in the hypothetical, but very seldom in the actual.

That said, there is a type of game that critics review, regardless of whether it is “likely” to be good: major releases. Games distributed by major publishers, games developed by well-known studios, games that cost a lot of money to make: these are all likely to recieve at least some critical attention, even if they seem about as promising as a self-released and ostensibly-low-quality Steam game. And, certainly, there are a small number of moderately-sized releases that do receive review scores of 5 or below; the 2023 game Wanted: Dead received scores of 4 and 5 out of 10 from several major publications.7 8 That said, major videogame releases seem mostly immune to these sorts of review scores. Even AAA games that release to lacklustre critical and popular response seem to mostly scrape by with scores of 6.5 or above (e.g, Days Gone, a game that seemed to be liked by approximately no one, and yet received relatively good review scores regardless9). So, when it comes to games with relatively-large releases, perhaps there is some truth in the afore-considered possibility: games with a sub-5 level of quality do not make it through development and publication. Either they are polished enough to land safely into the 6.5-and-above zone or they are aborted mid-development and are never released at all. There likely is some truth to this, at least in the domain of ‘moderately-sized’ (or greater) games.

However, regardless of why nearly all review scores fall in the 6–10 range, it remains the case that this practice limits their value. By doing so, we cede a full half of our measurement scale, muddling the interpretation of the scale and diminishing the interpretability of the scores that we do use. Consider: a scale that uses the entire 1–10 range has twice as many potential values to assign a game and so should be (approximately) twice as good at distinguishing between the quality of games. A scale that functionally runs only from 6–10 has far worse sensitivity for distinguishing two games of ‘similar quality’ and this problem is only exacerbated by our perverse fixation with assigning games scores of either 7 or 7.5. If we are only reviewing games that seem “likely” to be good (as seems to be the case), shouldn’t we expand the range of useable scores to reflect their true variation in quality? If we have already eschewed games that do not seem worthy of critical attention (i.e., the Weird Trash Steam Dregs), then what critical value is there in reserving the scores of 1–5 for them? Instead, rather than implicitly ignoring these sorts of games (as we currently do), we could explicitly ignore them and use our scales to accurately and sensitively evaluate the games that we are interested in critiquing. This would allow us to, for example, give a game a 5.5/10 as an earnest assessment, rather than as an indictment; we could more confidently measure games on their quality and compare those games on that metric, instead of attempting to cram every game between 6.5 and 10.

I present this argument equivocally because, in truth, I do not know where I stand on the matter. There are a variety of considerations that go into determining review scores other than the ones discussed thus far. Some of those considerations have nothing to do with the aesthetic exercise of evaluating a piece of media and then assigning it a score on a numerical scale. One such consideration is the way in which review scores are currently instrumentalized in the industry. Although a single critic and their review score does not determine the success of a game or the fate of that game’s developer, it does contribute to these things. Many developers’ jobs and bonuses are contingent on their game reaching that coveted Metacritic score of 80 or above. Publishing a review on a major platform with a score of, for example, 4/10 can have a genuinely negative impact on the developers of that game.10 Perhaps this is a valid argument to cede the bottom half of the review score scale. This issue does not mitigate the validity of the argument presented henceforth, but it might supplant it. In other words: I understand why critics are hesitant to give major videogame releases low scores, given the very real impact it might have on someone’s life. I would have the same hesitation.

But, luckily for me, I do not have a major platform. No one cares what review score I give a game, should I decide to do so. I have the full extent of critical freedom afforded to me by a complete and utter lack of audience or power and by a needlessly-extensive meditation on the practice of assigning review scores. So, why not practice what I preach? Why not undertake the hard work of earnestly and genuinely considering games I’ve played recently and assigning them review scores? After all this pontificating, what range of scores am I really comfortable using?

This is an excercise that I think is worth undertaking. So, what follows is a brief consideration of several games that I have played recently, accompanied by a review score. I will abide by the challenge articulated in the outset of this discussion, avoiding the use of a review score of 7 entirely. I will also only assign games an integer score between 1 and 10, thereby sticking to a true ten-point scale (albeit one where I contrivedly avoid the number 7). Readers who are not interested in receiving a full shotgun’s blast worth of micro-reviews may confidently peruse, skim, or skip to their heart’s content, and continue with the conclusion of the primary discussion presented below.

THE LEGEND OF ZELDA: TEARS OF THE KINGDOM

Despite having a small book’s worth of thoughts on Tears of the Kingdom, I actually find it to be extremely difficult to score. Most major publications gave it a perfect score or something very close to it but, as has been discussed, my opinion on the game diverged considerably from those major publications. That said, I certainly did enjoy the game—I mean, I adored its predecessor, and I spent a couple thousand words arguing that it is in many ways a misfit clone of its predecessor. I also played it for about a hundred hours, which is not something I would do for a game that I did not at least enjoy. The truth is that the score that feels most apt for Tears of the Kingdom is.. a 7. However, I will resist the urge to violate mine only rule in this first micro-review, and instead commit to either a 6 or an 8. A part of me can’t help but lean towards an 8 because how could it be a 6 it’soneofthegreatestgamesofalltimeyoucan’treallybesayingthatit’sa6canyou but then I think about all the many games that I like better than Tears of the Kingdom. I think about the wide array of ways in which games have surprised or delighted or charmed me, even with budgets or teams a fraction of the size of Tears of the Kingdom’s. I think about all the games that have struck me with their bravery or conviction or experimentation and I remember how utterly safe Tears of the Kingdom was (despite sort of also being a janky mess). I think about these things, I close my eyes and nod sagely, and I assign The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom a

6 out of 10.

FINAL FANTASY XVI

Ah, the sixteenth Final Fantasy. Now this is a game that demands 5000 words of contrarian contemplation from someone with too much time on his hands. And it’ll get it, very shortly. But at the risk of dipping into the fondue before it’s been properly heated, I will tell you that, in general, I found this game very disappointing. I wanted to like it, and I did enjoy its combat a great deal, but I ultimately found it to be a very empty experience. I thought its story had a ton of potential that was completely unfulfilled, I found its characters to be shockingly flat and forgettable, and I found its RPG systems to be paper-thin. I did continue to enjoy its combat throughout the entire game’s length and I found its boss battles and set pieces to be captivating to the very end, but the NPC-ping-ponging and side quest tedium between these moments left me feeling deflated and a little sad. For that reason, I bequeath Final Fantasy XVI a

4 out of 10.

POKÉMON TRADING CARD GAME

About 18 months ago, my brother and sister ordered me an Analogue Pocket for my birthday.11 It arrived a couple of weeks ago and so, since then, I have been messing around with a variety of different Gameboy (etc.) games. The one that got its hooks into me most was the Pokémon Trading Card Game, a Gameboy Color game that does exactly what it says on the tin: it has you play the Pokémon card game. I had never played this game and, frankly, had never really played the card game properly either, despite owning the cards as a dutiful child of the 1990’s. In the course of completing this game, I found out two things: (1) the Pokémon card game is a deeply flawed game that is overly reliant on luck and opening draws (even for a trading card game); and (2) the Pokémon card game is fun as hell. Despite the many flaws of the Pokémon Trading Card Game—some of which are due to age but most of which are due to poor choices in game design and development—I couldn’t help but find myself mildly addicted to it. As I wrote in my notes after finishing the game, “Card games are card games” and I am not someone who says no to card games. The game basically artificially restricts you to using a single deck (despite offering you several deck slots) because it doesn’t allow you to share cards between decks (even though every deck needs four copies of BILL and anyone who tells you otherwise is just trying to shark you). Cards are extremely difficult to obtain, especially in the quantity that one needs to reliably play them, and this deeply frustrates the deckbuilding experience, which is inarguably integral to the game. There are also a total of probably 40 opponents in the game12 and that’s it. That’s the game. You play cards against those 4013 opponents and there is nothing else. So it’s not exactly a fully-fleshed out experience. Despite all that, I really enjoyed my time with the Pokémon Trading Card Game and I fully intend to play the English fan translation of its sequel, Pokémon Trading Card Game 2: The Invasion of Team GR!, and soon. Thus, I flip a coin, get heads, and give the Pokémon Trading Card Game a

5 out of 10.

STREET FIGHTER 6

Street Fighter IV is the only fighting game at which I have ever gotten any good. I played it obsessively with my friends across its several iterations throughout my adolescence. I mained Sagat and Akuma and, when I was feeling daring, Sakura or Hakan. Like most people, I found Street Fighter V deeply disappointing and I never really bothered to play much of it. I found it a bit ugly and tedious and unfriendly and just never really felt motivated to spend much time with it. So, when I heard all the positive buzz from games press who had the opportunity to play Street Fighter 6 early, I couldn’t help but feel optimistic. I am happy to report that my experiences with Street Fighter 6 were in utter opposition to those with Street Fighter V: the game is friendly and engaging and instantly fun.14 Its mechanics are deep but approachable; its single-player campaign is surprisingly charming, even in its jankiness and occasional flatness or time-wastiness; its online multiplayer options are highly functional and inviting. I wish I was 16 again and had time to play it for 30 hours a week with friends, but even as an adult, I lovingly bestow Street Fighter 6 an

8 out of 10.

MIDNIGHT SUNS

Now here’s a game that doesn’t deserve several thousand words of contrarian contemplation, and yet is going to get them soon anyway. Strangely, this game was one of the impetuses for actually collecting my thoughts on games in a complete and polished essay-style format. As I played the game, I couldn’t help but ply several of my friends with essays’ worth of critiques and contemplations and complaints on the game, and I realized that both they and I would be better off if I just collected those thoughts elsewhere, where I could exorcise them from my addled mind without risking them hurting anyone. What’s unique about this game, however, is that—as near as I can tell—I’ve thought about this game more than anyone else.15 16 17 Again, at the risk of serving the basashi before it has thawed, I will tell you that this is a game whose fun is only matched by its bizarre flaws. For every bit of genius in its core gameplay and loop, there is an utterly inexplicable and completely misguided design decision that is so transparently-bad that I can only assume it was caused (or failed to be prevented) by some failure of management or production. Midnight Suns is a big beautiful mess, a monkey’s paw of a game that I will eventually discuss in greater length than probably anyone else, and so I boyishly lob it a

5 out of 10.

THE SEXY BRUTALE

The Sexy Brutale is a neat little mystery-puzzle game with a lot of great ideas, but whose execution is often shoddy. The whole thing takes place during a time-looped masquerade at this lavish mansion-slash-casino. It has this great setting and style and this charming (if under-developed) cast of characters. The puzzles and their solutions (when deployed correctly) were often quite enjoyable and the story was generally quite engaging (if occasionally a bit ‘unearned’). The game’s main problem is an overarching sense of friction: things often don’t quite work the way you want them to or the way you’d expect and, often, there is very little freedom in terms of experimentation or puzzle soutions. There is precisely one solution to every problem and you often just find it by clicking on The Right Thing. Often, you can recognize what the solution is quite quickly, but it will take you several attempts to input the solution in the precise way that the game desires. This really sucks the air out of the room and deflates the whole “aha!” puzzle-solving experience. The game never really makes you feel like a genius in the way that Return of the Obra Dinn or The Witness do,18 but I also can’t deny its charm, style, and panache, so I palm and then stealthily pass The Sexy Brutale a

4 out of 10.19

DEATH’S DOOR

Uh oh. I can already feel the temptation to break my rule on this one. ohgodthisgamewantssobadlytobea7it’s the most 7 game i’ve ever playediknowit’sa7—Death’s Door is a lovely little game. It’s charming, cohesive, it’s got a great tone and its combat and difficulty level are both very satisfying. The story was good, the secrets were fun to figure out, the characters were great, and the progression hooks were fairly compelling. I have no real complaints about it, other than that it compares mildly-unfavourably to other games of its ilk: Hyper Light Drifter, Fez, and the soon-to-be-discussed Tunic, for example. Other games in this category—games of which I am very fond, as it happens—were just a little more laden with secrets, were a little more captivating in their combat, were a little more obsessively-designed to provide the optimally-rewarding puzzle-solving experience. Breathing deeply and steeling my resolve, I grant Death’s Door a slightly-inflated

8 out of 10.

ELDEN RING

Elden Ring is one of the greatest games ever made. It is probably the best open-world game ever made (even if it isn’t necessarily my favourite FromSoft game20) and it is probably the best game yet made by one of the most influential studios currently operating. Elden Ring is so good in so many ways that it feels almost trite to discuss, especially in brief. It’s fun, surprising, hilarious, challenging, and has incredible lore. It has so many carrots to incentivize exploration and experimentation, all while respecting your time, intelligence, and need for novelty. Its final third is filled with its best bosses, toughest challenges, and most compelling levels, and thereby completely justifies its considerable length. It also iterates on the previous souls-like FromSoft games by making the bold decision to contain almost no unnecessarily-annoying-and-tedious-bullshit, which had theretofore seemed to be an integral (if diminishing) part of FromSoft games. As a lowly tarnished of no renown, I have no choice but to bless Elden Ring with the Grace of a

10 out of 10.

CALL OF THE SEA

Call of the Sea is an adventure puzzle game with a neat story, a good aesthetic, good writing, and decent puzzles. I found its plot intriguing and I couldn’t help but feel invested in the protagonist, her plight, and her lost husband. This investment was earned through several beautiful moments, scenes, and pieces of music, and overall I found it to be quite a moving experience. When the puzzles are good, they are good, but when they are not good, well.. they are absolutely not good. For many of the puzzles, I found myself brute-forcing the final 10–25%, which can really spoil the experience. Each time that occurred, it felt like I had actually ‘solved’ the puzzle (in my mind), but that there was some last little bit of finesse required from me that never quite made itself apparent. Perhaps I am accidentally just reviewing mine own intelligence here,21 but I couldn’t help but feel that the game needed additional playtesting to really nail the puzzle-solving experience. The rest of my notes on this game consist primarily of several hundred words of detailed complaints about how unnecessarily- and agonizingly-slow this game’s walk speed is. I give my Dear Old Pal Call of the Sea a

6 out of 10.

NEON WHITE

There are many things that make Neon White such a compelling experience: its addictive and meticulously-designed gameplay loop; its intriguing and obsessively-perfected level design; its delightfully-strange and only-occasionally-cringy writing. But there is one reason above all that Neon White is such an excellent game: that it has the guts to be scored exclusively with the only type of music that should ever be used in videogames: breakcore. The music is absolutely quintessential to Neon White’s intoxicating, hypnotic, transcendental gameplay. It’s so good that I can forgive the baby’s handful of flaws that mar the game, like the slightly-overwrought (if mostly charming) writing and the few deeply tedious boss levels. After several minutes of repeatedly trying to do so perfectly, I give Neon White an

8 out of 10.

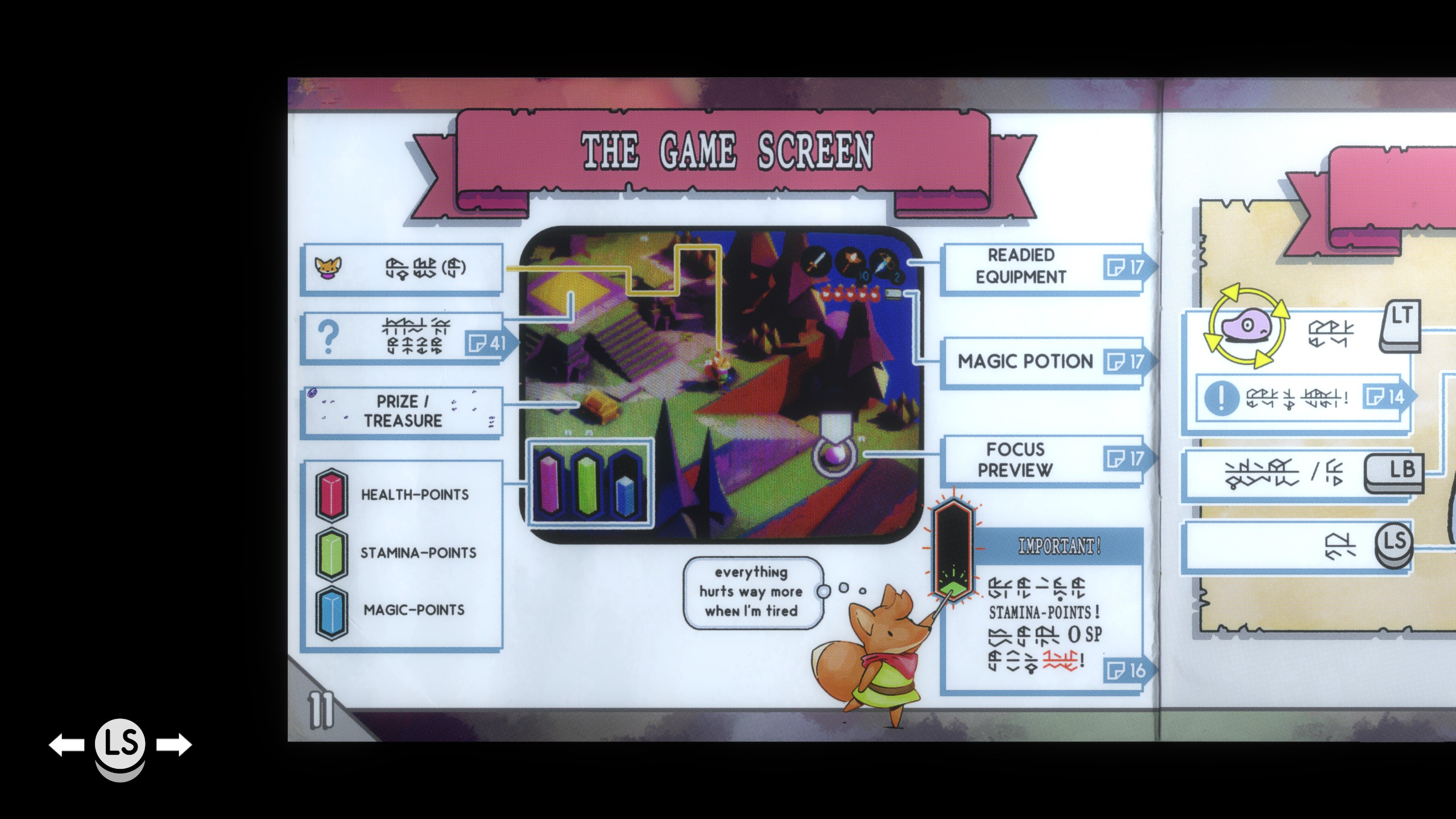

TUNIC

Tunic is a lovely 2D Zelda clone, except in the many many ways that it is distinctly not that. It features one of the coolest and most memorable mechanics I have encountered in years, in the form of an instruction manual that you construct using pages found in-game. These pages explain to the player, mostly in a foreign language, the game’s various mechanics—they are generally all available to the player already, the player just doesn’t know how to use them. Once you understand these mechanics a little better, you can also use them to back-translate the foreign language so that you can understand other aspects of the game better. This all culminates in one of the coolest final puzzles that I have ever encountered and completed.22 The game has wonderful music, beautiful art and animations, mostly-tight combat, and a captivating story. My few small complaints about crowded controls or bizarre pathing decisions23 notwithstanding, I adored Tunic, and so I crown it with a

9 out of 10.

OVERBOARD

Overboard is a charming game with an irresistable premise: you have thrown your wealthy husband overboard and you must escape suspicion and successfully inherit his wealth and life insurance payout. It really commits to this premise and offers a shocking level of freedom. Each time I played the game, I discovered some new route or option, and by the end I had discovered a variety of ways to accomplish my goal, along with a few alternative endings… The game is not without its faults, however. The writing is good but not incredible—it’s the game itself that is doing the heavy lifting, as opposed to the writing. And once you do know the broad strokes of the game, it can be maddeningly-tedious and repetitive to find the exact path that you want. I also personally despised the music and sound design, which (in this case) is a matter strictly of personal taste, but literally no other game has ever aggravated my misophonia quite so much as did Overboard. Thus, I have broken into Overboard’s cabin and left it with a

5 out of 10.

Alright, that’s quite enough of that.

This was an interesting exercise to conduct. I had genuinely not decided on any of these numbers (aside from, perhaps, Elden Ring’s perfect score) before beginning to write these micro-reviews and so, for each game, I legitimately had to consider: on a real 10-point scale that was used to measure the quality of worthwhile games, what score would this game deserve? How does (my experience with) it compare to (my experiences with) other games? If I give a game an 8 out of 10, am I really saying that it is “two points” (whatever that means) below some of the most impactful gaming experiences I’ve ever had? If I am saying that, then I should probably be a little more austere with how many 8s I dole out (and, for that matter, how many 7s).

I have to admit though that it does make me uncomfortable to use these sorts of numbers. It feels ‘wrong’ to give a major game like Final Fantasy XVI a 4/10, a score lower than the one I gave to a Gameboy game from 20 years ago that was probably developed primarily to market the far more lucrative eponymous card game. It also makes me uncomfortable to give Tears of the Kingdom such a low score when others have casually observed that it might be the greatest game of all time.24 It even makes me uncomfortable to give a game like Midnight Suns—a “big beautiful mess”—such a low score when I enjoyed it so much, but I couldn’t very well give it the same score as Tears of the Kingdom.25

I will say that the arbitrary rule of avoiding the number 7 entirely ended up artificially making this task more difficult and probably only served to make my scores less precise. That said, it was probably good that I didn’t have access to that particular lifeline, at least for this exercise. Perhaps critics shouldn’t be forbidden entirely from assigning a review score of 7 to games, but maybe it should just be restricted in some way. My suggestion is that everytime a critic gives a game a 7, they also have to donate $100 to charity. That way, they have to really mean it, and they can’t just use it as a means of avoiding strong declarations about a game’s quality.26

It’s also worth noting that I fundamentally enjoyed all of the games discussed, even when I was disappointed with them (i.e., Final Fantasy XVI). I just also think that if we are going to undertake the (admittedly-foolish) task of assigning numerical scores to evaluate the quality of a piece of art, we need to be realistic and honest in that process. If we believe that some games are masterpieces and deserve a score of 10/10, and we want to actually commit ourselves to that evaluation, then we need to accept that there are also going to be games—games that we like—that deserve scores more like 5/10. The most positive aspect of this exercise was realizing how useful it was to use the whole scale, rather than attempting to cram every game that I like into numbers between 7 and 10. It helped me to meaningfully distinguish between these games (games which, I can’t stress enough, I liked) and helped me to be more honest and precise in my evaluation. It is far better to devote the score variance in our scale to meaningfully distinguishing between an array of good games than to cram them all into a small handful of values, ceding all of that meaningful score variance to hypothetical-but-never-actually-reviewed “bad” games.

Ultimately, I remain equivocal on assigning review scores, both as it is currently practiced and in the manner proposed herein. I cannot deny that the practice has some critical and popular value. Nor can I deny that the practice is itself fun. That said, assigning review scores when you know that it might impact the success and continued employment of a game developer seems like a deeply unpleasant undertaking. I cannot fault individual publications for giving up on the practice entirely and nor can I fault publications for ceding the lower half of the review score scale. Even if review scores did not have direct effects on the lives of individual game developers and even if the review score scale was ‘redefined’ in the manner I have proposed, game review scores would remain a fairly limited tool. They are useful heuristics, especially between familiar parties (be they two friends or a critic and her audience), but convey very little when stripped from context. Unless one understands the game, understands at least something about the critic’s taste and perspective, and understands the industry context in which the game and the accompanying score emerged, one is unlikely to learn much from a review score—like, for example, whether one should play that game. I am not yet certain how I will handle the issue of review scores in the future, whether I will continue to use them in the popular manner or in the new proposed style, or whether I will eschew them entirely. But one thing about review scores remains certain: The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom is a 7 out of 10.

Some final errant thoughts:

One way to improve review scores—both making them more valid and slightly mitigating the harm that they have on the industry—would be to use a multidimensional measure. The current unidimensional measure uses a single number between 1 and 10 (or whatever the case may be) to evaluate a game in its totality—its story, its gameplay, its appearance, its approachability, and universal appeal. We all implicitly understand that this is not the optimal way to assess a work, but we accept it because it is simple and it makes review scores more functional as a heuristic (i.e., “Did you hear that Slay the Spire got a 9/10 from IGN?” instead of “Did you hear that Slay the Spire got a 9/10 on gameplay, a 6/10 on music and sound, a 10/10 on replayability…”). As it happens though, multidimensional review scores used to be quite common. Publications like EGM, Famitsu, and GamePro all evaluated games on a variety of metrics, such as “Visuals”, “Sound”, “Ingenuity”, “Replayability”, or the inimitable “Fun Factor”. Some publications even had multiple reviewers for each game, which is a level of rigor that is certainly laudible, if not really feasible in the modern industry landscape. If this sort of multidimensional review score was to be revived, it is not immediately clear to me which dimensions should be employed. On first blush, I recoil somewhat at these early attempts at multi-dimensional review scores. But after a moment of consideration… why shouldn’t we evaluate games based on visuals, sound, replayability, and fun? Does that not capture so much of what we love about games? These dimensions seem a bit crass, perhaps, but as we have already discussed: the process of assigning review scores is inherently crass. Maybe some simple multidimensional measurement would make for much more interesting and communicative review scores.

The games featured in my ‘micro-reviews’ were games that I played throughout the last two years or so. Many of the games discussed are ‘smaller-scale’ games, partly because I can play many more of those types of games, partly because I find them to be more interesting to evaluate, and partly because they are easier to discuss and evaluate in an efficient way. I also played God of War: Ragnarok and Fire Emblem: Three Houses in 2022, but those games feel so much more difficult to capture with a single numerical score and a hundred words or so. This starts to intimate an even more troubling solution to all of this review score trouble: using different types of scales for different types of games. Although that might make for a fun thought exercise, it does not seem to me to be a feasible or desirable solution. No, at that point, surely the erasure of all numerical review scores would be a preferable resolution.

In its scoring system definition, Game Informer literally defines 7 as “average.” I still don’t know whether 7 (or 7.5) is the modal score in game reviews, but I thought it was funny to encounter this particular definition (after having already written this essay in its entirety).

Footnotes

7.5 is just as cowardly, if not moreso.↩︎

I imagine that these data are both out there and readily accessible but, for the moment, it is better for me not to know.↩︎

This idea is complicated and contentious enough that it does tempt one into the swamps of True Aesthetics Discourse: What is a 6/10 game? Is a game a 6/10 game if it is given that score by one critic? What if it is given that score by every critic? If indeed a “6/10 game” does exist, is it ever possible for us know if a game is a 6/10 game? What does it mean for a game to be ‘better’ than another game? Rather than wrestling with these questions, let us put these more pernicious questions aside for another day, and accept the most simple and lay-accepted definitions intimated. A “6/10 game”, for our purposes, is a game that many or most people have (rightly or wrongly) assigned a score of approximately “6/10.”↩︎

Many people—myself included—prefer a scale that ranges from 1 to 10 because it provides greater granularity and precision (or so we suppose) than one that ranges from 1 to 5. It is ironic, then, that a scale that functionally ranges from 6 to 10 is also a five-point scale.↩︎

I am avoiding the use of the term “objective” here on principle because I see the words “objective” and “subjective” misused far more often than I see them used correctly. For that reason, I try to avoid them whenever possible, lest I be misunderstood and further contribute to the misconception of those terms.↩︎

At least, I assume that this is the common perspective, given the evidence (i.e., most critics are not publishing these sorts of reviews).↩︎

This is neither here nor there, but I have to say that receiving a 4/10 from IGN and a 7.5/10 from Destructoid makes me very tempted to play this game. I have nothing against IGN, per se, but this particular pair of scores from this particular pair of publications is an indication that the game is at least interesting, if not “Good” in the traditional sense.↩︎

I struggled to think of an example to support this assertion (even though I know that they exist) and I am not even sure as to whether this is a good example, as I have no idea how to evaluate the ‘size’ of this release. Is it a AA game? It sort of seems that way but it also doesn’t have a Wikipedia page. Its developer, Soleil Game Studios, and its publisher, 110 Industries, also do not have Wikipedia pages. How big can a game really be if neither it, nor its developer, have Wikipedia pages? I realize that this is a sort of trivial thing to focus on, but I am not sure how else to evaluate the ‘size’ of a game.↩︎

In contrast to Footnote 7, receiving a 6.5/10 from IGN and a 7.8/10 from Game Informer makes me deeply uninterested in playing a game.↩︎

(even though we don’t actually know exactly how Metacritic scores are calculated)↩︎

For those who do not pay attention to this sort of thing, the Analogue Pocket is essentially an artisanal Gameboy. It plays games from the Gameboy, Gameboy Color, and Gameboy Advance systems, but with a much better screen and without any sort of emulation. It is extremely cool.↩︎

The source for this estimate is: my heart. And also: vibes.↩︎

See Footnote 12.↩︎

It’s, uhh, still a bit ugly unfortunately.↩︎

potentially including the developers↩︎

just kidding!↩︎

i’m not sure if i am kidding↩︎

It is perhaps unfair of me to compare The Sexy Brutale to (what I consider to be) two of the greatest puzzle games ever made but, in my defence, the gameplay sort of does invite this comparison (at least with Obra Dinn, if not with The Witness).↩︎

Here is a fun little insight into the subject-emphasizing (see Footnote 5) experience of reviewing games: very shortly before playing The Sexy Brutale, I read a novel with a very similar premise and a shockingly-similar denouement to that of the game. I found the novel slightly disappointing, if also largely enjoyable. I think that experiencing these two stories in such close chronological proximity had a mildly negative impact on my experience with The Sexy Brutale. It was just a bit strange to experience such similar stories in such different mediums so close in time and I have to imagine that that compromised my experience with the game, at least slightly. I will not reveal the name of that novel, lest I spoil either the novel itself or The Sexy Brutale, but if you come to my house and knock on my living room window, I will tell it to you.↩︎

In fact, it is probably my third favourite FromSoft game. If you’d like to know the first two, you can come to my house and knock on my living room window and I will tell them to you.↩︎

In a sense, all criticism is an unwitting review of oneself. Incidentally, it also seems to me impossible to effectively critique any piece of art without betraying deeply personal information about oneself—often information to which the critic may not even have explicit access.↩︎

The haters are right, I never did finish the shipwreck puzzle in The Witness.↩︎

Minor structural spoilers: if you collect all of a certain collectible, the game locks you out of its “bad ending”, which actually prevents you from fighting the final boss entirely. I had to manually edit my save file just to attempt to fight the final boss.↩︎

To be clear, I’m not afraid of disagreeing with others or with the general consensus. It’s just that one can’t help but feel like one has missed something crucial when one’s perspective deviates from the general consensus this strongly.↩︎

…could I?↩︎

Also: according to the new standard of review score measurement proposed herein, games with less than a 7 can still be considered good games.↩︎