The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask was released in the year 2000 as a sequel to The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, one of the most influential and beloved games of all time. It was developed in under two years, made possible by the reuse of assets and gameplay elements from its predecessor. Alongside the challenge of this highly-accelerated development cycle was one far more unique and (perhaps) daunting: how does one develop a sequel to one of the best games ever made?

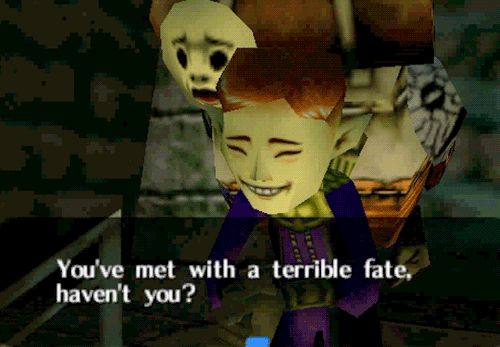

I am not sure exactly when I played Majora’s Mask for the first time. I know that before I played it, I was fascinated with its art, presented in luscious multi-page spreads found in an issue of Nintendo Power left at my house by a stranger on New Year’s Eve.1 Its dark tone instantly intrigued me, presenting perhaps the first indication of my future as a fairweather mall goth. And, indeed, the game delivered on the Dark Promises made in that centerfold. Its putrid vibes are evident from the start. It is a game that oozes omens and curses,2 offering the player pestilence and corruption and dread. I adored it. It remains my favourite entry in the Legend of Zelda franchise to this day. It was strange and it was hostile and it was beautiful and its moon is still horrifically iconic. Even as an adult, I cannot really watch the mask transformation scenes without averting my gaze.3

For the uninitiated, Majora’s Mask provides two unique twists on the franchise. First, it has an in-game countdown clock, the end of which brings the moon crashing down into the earth, ending the game and presumably the world. Players must complete tasks within the three in-game days provided and must travel back in time, to the beginning of the first day, before the end of the countdown. Each time the player travels back, the world generally resets, and only a small handful of things remain changed. Second, the game provides players with a massive variety of masks, each of which has its own unique uses and effects. Despite its hurried development and despite the astronomical expectations set by Ocarina of Time, Majora’s Mask punches far above its weight class. Its mechanics are experimental and yet shockingly well-implemented; its themes are complex and yet are eloquently wed to the aforementioned mechanics (in a way that we sometimes pretend is unique to modern games4); its story is touching, its characters charming, and its world so richly depicted. It does all this while striking a haunting tone and a uniquely dark aesthetic. For so many reasons, it is such an improbable game, and I still find it shocking that it exists at all, let alone that it managed to be as good as it was.5

Secure in the knowledge that I will never have to struggle with the herculean task of making a sequel to a Great Work of Profound Meaning and Influence, I think that the undertaking merits some contemplation. How does one improve upon—or at least meaningfully follow-up on—something that is widely considered to be near perfection? Given a span of less than two years, how does one iterate on (what was at that time) a work of staggering achievement in design and technology? It is certainly beyond me to answer this question in any sort of Broad or True sense, but I think that Majora’s Mask demonstrates one viable strategy: avoid “improvement” or “iteration” altogether. Rather than attempting to “upgrade” the experience, provide a “sidegrade” in the form of something completely different. By endeavouring to experiment, rather than iterate or incrementally-improve, Majora’s Mask deflects attempts to compare it to its Unparalleled Predecessor, providing an experience that is altogether too orangey to be evaluated for its appleness.6 Of course, this strategy was never fool-proof, and there are undoubtedly examples of it failing elsewhere in the world of Oh My God How Do We Make A Sequel To This games,7 but Majora’s Mask represents a strange and inspirational demonstration of how to provide a sequel to Something Great.

As it happens, another entry in the Legend of Zelda franchise was recently released: The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom is a “direct sequel”8 to another Great Work of Profound Meaning and Influence, The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. At this point, it would be trite to expend much time in detailing the import and quality of Breath of the Wild (though it will happen incidentally throughout this discussion), but suffice it to say that it is a game that I enjoyed a great deal when I first played it on the Wii U in 2017 and then again when I played it on the Switch in 2020.9 I was sceptical of it when it was first announced and previewed, as I am inherently sceptical of open-world games, but ended up playing it soon after launch, having been convinced by Jason Schreier’s excellent review. Breath of the Wild was developed in around five years, which is, in retrospect, quite an impressive feat, considering the game’s grandiosity and uniqueness within the franchise. It was and is one of the greatest open-world games ever released,10 and, like its much-older sister Ocarina of Time, became deeply influential and widely beloved. Again, the Legend of Zelda development team were asked the question of how to develop a sequel to one of the best games ever made. Their answer came after about six years of development, in the form of Tears of the Kingdom.

Like Majora’s Mask, the development of Tears of the Kingdom benefitted from the reuse of the engine, assets, and mechanics of its predecessor. Indeed, it reuses the massive sprawling map and the (admittedly-boring and homogenous) enemies of Breath of the Wild, thereby providing players with an experience that is altogether much more “familiar” feeling than did Majora’s Mask. However, in contrast to Majora’s Mask, Tears of the Kingdom does not avoid “improvement” or “iteration”. Instead, it attempts to build on—or perhaps supercede—its predecessor by providing something that is Approximately Better. The extent to which it accomplishes this task, however, is unclear to me.11

The main way in which Tears of the Kingdom attempts to iterate upon Breath of the Wild is through the introduction of a crafting mechanic. Although very simple machines were possible to build in Breath of the Wild, Tears of the Kingdom fully leans into this design space, replacing most of Breath of the Wild’s major player mechanics with this crafting.12 The possibilities provided by these crafting mechanics are seemingly endless, as has been demonstrated in the manifold gifs and videos depicting the increasingly-complex and horrific means of torturing koroks. For a player interested in sandbox experimentation, these tools are undeniably invaluable. But how are they for.. everyone else? How are they for players who are not necessarily interested in “making their own fun” or in spending hours exploring and perfecting different machines (that are ultimately doomed to disappear once you walk away from them for about 20 seconds)? My (likely-unpopular) answer is that: they are not great.

Tears of the Kingdom is a game that has one very cool (if imperfect) idea and the misfortune of being the sequel to a game with a great number of cool ideas. Although many of these cool ideas remain present in Tears of the Kingdom (e.g., shrines), it is difficult to “give it credit” for these ideas, given that they are generally implemented in a fashion identical to that of its predecessor. Consider: although Ocarina of Time deserves to be lauded for its groundbreaking “Z-targeting” enemy lock-on system, Majora’s Mask does not. Although many of the parts of Tears of the Kingdom that are lifted directly from Breath of the Wild remain interesting and enjoyable, I do not find it to be critically-fruitful to linger on them, at least not in the present discussion.13 Instead, we must evaluate that which has been added, that which attempts to iterate and improve upon the predecessor.

In this case, that which attempts to iterate and improve is the collection of crafting mechanics that, to put it bluntly, I find wanting. Although the first time you (carefully, tediously, meticulously) successfully build a vehicle in Tears of the Kingdom is a triumph, the second time is a nuisance. The third time is a downright bore. The fourth time generally just does not happen as, by this point, you’ve realized that it would be faster and simpler just to sprint or glide to your destination. The enervation of crafting a vehicle is mitigated somewhat by the introduction of the Autobuild mechanic, which allows you to automatically build some of your previous creations (along with a set defined by the game),14 but this represents more of an admission of guilt than a true solution: “We know this can be really annoying. Uhh, does this help?”

Machines often do not work how (it seems like) they should. One of the main ways you enable them is by striking them with your weapon but many weapons will destroy the machine with a single strike. Even when flawlessly constructed and enabled, sometimes they malfunction or overturn or explode, snagged on some invisible seam of level geometry or else possessed by some trickster phantom. Even after playing over a hundred hours of the game, I could not reliably build and pilot a flying machine to great effect. Even in the final (inexplicably-tedious) hours of the game, as I explored its final sky archipelago, I still could not build and use a flying machine effectively. After several wasted minutes and a failed attempt, I simply used a spring to shoot myself into the air15 and glided to my destination. What odds.16

Ultimately, these imperfections in implementation are not the main problem with the crafting systems in Tears of the Kingdom. The problem is the mismatch between them and the other elements of the game. These systems undoubtedly provide ample emergent gameplay possibilities, but this emergent gameplay is not clearly aligned with the game’s traditional action-adventure gameplay or its (mostly-unremarkable) narrative. How does crafting and vehicle-building enable exploration, over and above the systems that are already in place (e.g., horses, gliding, climbing, jumping)? The answer is that they do so in only small and often unremarkable ways. A flying machine may allow you to reach remote sky islands (assuming that it does not disappear from underneath your feet before you arrive) but most of them can be reached more easily by using sky towers, gliding, and already-unlocked islands. A vehicle may allow you to traverse the hazardous underground depths (assuming that it does not encounter any of the hostile terrain that covers the underground expanse) but it would probably just be simpler to sprint and glide to your destination. A weapon fused with a monster part—the other new major crafting system—may do more damage and have better durability, but its effect on combat is ultimately minimal, less likely to change the way in which you fight than it is to simply make a fight shorter and less unpleasant. Furthermore, these systems have little to do with the narrative of Tears of the Kingdom. Crafting, weapon fusion, vehicle piloting: none of these gameplay elements relate to the narrative or its themes in any clear or important ways. Indeed, the world seems to mostly ignore these abilities of yours. Denizens of Hyrule (outside of the Yiga Clan) generally aren’t aware of the concept of vehicles or fusion (enabled as they are by ancient mystical powers) and they don’t seem terribly interested in engaging with them further. Link’s newfound abilities to build and fuse and invent are of effectively zero interest or impact to Hyrule or her inhabitants.

This mismatch—both between distinct gameplay elements, and between narrative and gameplay—contrasts unfavourably with Majora’s Mask, which elegantly integrates its novel mechanics, its narrative themes, and its world. Briefly: the world, the characters, the stories and mechanics of Majora’s Mask all meditate on the idea of impermanence and transience—transience of identities, transience of circumstance, transience of values, and of strengths, and of relations. Link was never headed to Termina (the world of Majora’s Mask), he was only passing through. Clock Town, the spiritual and literal centre of Majora’s Mask, is in the midst of preparing for a festival. It is filled with temporary buildings, itinerant guests, and relations of convenience. Characters, too, find their identities and relationships to be in flux: the game’s antagonist, the Skull Kid, struggles with rejection, but ultimately copes by shutting himself off from the world, casting the two relations that he does have (friendships with the fairies Tatl and Tael) into doubt. Perhaps most of all, Link experiences the transient nature of identity, using literal and metaphorical masks to modulate how he interacts with his environment and the people in it. And, ultimately, when he plays the Song of Time and returns to the Dawn of the First Day, it will all come undone. The people he has met and helped, the evils he has defeated, even the personal wealth he has accumulated, will all be erased, replaced again with a sense of dread and a little bit of melancholy. There is much else to say about the eloquent integration of gameplay, plot, and world presented by Majora’s Mask—somewhat reminscent of a certain icon found elsewhere in the franchise—but it need not be stated here. Instead, let this brief discussion illustrate the ways in which a Zelda game with novel mechanics can integrate its gameplay and its narrative, and how it can serve as an effective sequel to a Great Work, that we may return to the discussion of how Tears of the Kingdom does not.17

Having evaluated the attempts of Tears of the Kingdom to iterate upon its predecessor, let us now consider how it attempts to improve upon its predecessor. In short: it does not. Many of the flaws present in Breath of the Wild remain present in Tears of the Kingdom. Some of them are provided with foolish bandaid solutions. Others are left unaltered. Still others are emphasized and ratified, seemingly because the developers are unable or unwilling (likely the latter) to recognize them as flaws. For example, consider one of the most prominent problems in Breath of the Wild: its weather system. One of the game’s biggest, if simplest, innovations was allowing players to climb nearly any surface. However, random bouts of inclement weather would literally disable this feature, resulting in players either taking an alternate route or waiting out the rain.18 Tears of the Kingdom maintains this flaw, but provides a niche late-game solution. If you complete a lengthy globe-spanning questline, you will be rewarded armour that when upgraded twice, will finally allow you to avoid slipping while climbing. New cookable foods and elixirs can also provide some resistance to slipping, but only some (which, in practice, is as good as none). Other issues with the original game are left unchanged: everything takes far too many button presses, far too much useless menu navigation, far too much of a player’s real-life finite hours of existence. Cooking food, purchasing items, changing clothes, fusing weapons or arrows, upgrading equipment: each of these mundane tasks is unnecessarily slow and tedious, despite being done hundreds of times across a playthrough. There is no reason—at least, not one that is obvious to me—to leave these systems unchanged in Tears of the Kingdom. Why not allow the player to specify clothing loadouts, given how often they are changing them? Why not allow the player to mass-craft new types of arrows, given that it’s ostensibly one of the new major mechanics? And so on and so forth. Ultimately, Tears of the Kingdom does not actually seem terribly interested in improving upon its predecessor.

In fact, one of the most unusual aspects of Tears of the Kingdom is how it doubles down on a system from Breath of the Wild that was, at best, “divisive”. I speak, of course, about weapon durability. Weapons in Tears of the Kingdom still have the desperately-finite (and inexplicably-invisible) durability of those in Breath of the Wild and, indeed, there is now a contrived narrative reason to justify equipment having even worse durability. For reasons that are not really explained, nearly all of the weapons in Hyrule became “decayed” during the inciting events of the game. To address this, the player is encouraged to fuse things to their weapons, increasing their durability and attack, and occasionally altering their use in combat. Although there are a handful of fun and interesting ways in which to use this system,19 in practice, it generally provides the same enervating experience as did Breath of the Wild, albeit with more ritual. I have to assume that this was an attempt to ameliorate the weapon durability system, but it fails to address the ultimate and pervasive flaws inherent to the system, and so ends up only lampshading those flaws. Weapons still represent an annoyance to players, ostensibly encouraging them to experiment with different types of weapons, but ultimately just forcing them to use whatever garbage they’ve got lying around for the 20 strikes that it will provide before moving onto the next. This has the ironic effect of preventing players from ever getting used to the use of unusual weapons and from experimenting with the nuances of the different weapons and their movesets. It also has the egregious downstream effect of devaluing one of the main “carrot” systems in action-adventure games: rewarding player exploration with new weapons or gear. In Breath of the Wild and Tears of the Kingdom, player curiosity, exploration, or ingenuity is usually rewarded with one of a few different pieces of fungible trash: a disposable weapon, shield, or bow; some forgettable crafting material; perhaps some rupees. On a very rare occasion, players are graced with a (legitimately-rewarding) new piece of clothing, but only very seldom. No, you can be quite confident that your reward for exploring a little nook or solving a little puzzle will be another piece of disposable trash, soon-to-be-used and forgotten, completely indistinct from any of the other garbage you’ve been “rewarded.”20

In these ways (and others), Tears of the Kingdom generally fails to improve on its predecessor. It allows its flaws to remain unmitigated and, in some cases, it devotes even more game design space to emphasizing these flaws. Thus, given Tears of the Kingdom’s refusal to improve on Breath of the Wild, and its interesting (if ultimately misguided) attempt to iterate on its predecessor, some may feel that it actually qualifies more for the sequel strategy outlined in the introduction to this discussion. In other words, perhaps Tears of the Kingdom was an attempt to “sidegrade”, instead of upgrade, and experiment, instead of iterate/improve. Although I can see the argument for this conceptualization, I ultimately find it difficult to entertain, given how closely the game resembles Breath of the Wild. The world of Tears of the Kingdom, its narrative structure and core gameplay loop, its characters and antagonist and themes are all mostly lifted directly from Breath of the Wild. In many cases, these aspects of the game are functionally indistinct between the two releases (e.g., seeking out four Champions/Sages). Instead, to me, Tears of the Kingdom feels like a game that was developed in parallel to Breath of the Wild, perhaps in a nearby alternate timeline. Instead of developing the “chemistry engine” of Breath of the Wild, the developers created the fusion and crafting system of Tears of the Kingdom. Instead of seeking four Champions and their Divine Beasts, Link seeks out four Sages and their Temples. Instead of building up to a fight with the uninteresting and completely-flavourless Big Bad of Calamity Ganon, Tears of the Kingdom builds up to a fight with the uninteresting and completely-flavourless Big Bad of the Demon King, Ganondorf. Instead of experimenting with the ancient technology of the Sheikah, Link experiments with the ancient technology of the Zonai. The game feels less like a sequel to Breath of the Wild and more like its companion: a Legend of Zelda Red and a Legend of Zelda Blue.

These parallels would genuinely be sort of incredible, if they weren’t also deeply disappointing. What’s especially bizarre is that the game fails to be a sequel even in many basic and obvious ways. Its characters mostly ignore the events of the previous game. No one seems interested in or curious about the immense similarities between all of these events. There is no clear relationship drawn between Calamity Ganon and the Demon King, Ganondorf; between the ancient Sheikah and the ancient Zonai; between the four Champions or the four Sages. Character arcs from the previous game—namely, Zelda’s—are left untouched in favour of a new and unrelated storyline (albeit one with no real character arc).21 The game even opens with a similar (if deeply inferior) tutorial zone to that of Breath of the Wild’s Great Plateau. To anyone not paying close attention, the plot, characters, and world of these two games are functionally indistinguishable. To someone paying close attention, they’re.. well, they’re still basically interchangeable. If this game had come out in place of Breath of the Wild in 2017, I think that it would have received effectively the same reaction as Breath of the Wild did, and so in that regard, I cannot in good conscience argue that Tears of the Kingdom is a bad game. It’s just not really a sequel, is it? It’s sort of just a slightly different instantiation of the game we all already played. It has very little to say or add, narratively-speaking. Mechanically, it has one thing to say, though it comes at the considerable cost of replacing several interesting and fun mechanics, and its payoff is, I would say, inconsistent.

The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask regularly and unabashedly provides players with advice, often in the form of a first-person view of the Happy Mask Salesman. “Believe… Believe in your strengths…” “Have faith.” The game is instructing the player directly, both in how to play the game and in what lessons to take away from it.22 In a sense, the developers were also speaking to themselves, vis à vis the development of Majora’s Mask. “Surely you should be able to do something. Believe in your strengths.” They recognized the strengths and weaknesses of the unique position in which they found themselves and were able to capitalize on them. I am not sure what the credo of the Tears of the Kingdom development was. I’m not sure what game they were trying to make or exactly how they intended to develop a sequel to one of the greatest games ever made. I remain puzzled and frustrated with the game that they did make. It is undoubtedly a good game, but it is also a game that I have played before (twice, in fact), and perhaps more importantly, is not something that I haven’t played before. What makes Majora’s Mask so special and memorable and successful as a sequel is how unique and surprising it is. When Ocarina of Time zigged, Majora’s Mask zagged. It embraced experimental mechanics and strange tones and labyrinthine quest designs in a way that few games—let alone major Nintendo franchises—have the courage to do. “Have faith.” Tears of the Kingdom is the antithesis of this design philosophy, a game that is essentially the v1.1 of its predecessor. It is a young boy trying to copy his cool older brother but failing, the clothes ill-fitting and the affectations too clearly inauthentic.

Some final errant thoughts:

It is unthinkable to me that the developers thought it wise to require the player to speak to a sage in order to use their power. In practice, with four (or more) NPCs swarming around you in the heat of battle, unexpectedly appearing and disappearing, essentially indistinguishable from one another due to being an identical colour, it is completely unviable. These abilities could so easily have been relegated to a radial menu or to context-sensitive prompts. I cannot imagine how this got through playtesting.

There are a small handful of facts in this discussion that are technically (if only slightly) incorrect, in order to make it approximately spoiler-free. These slight inaccuracies should not compromise the arguments presented, though they may prove infuriating for the terminally-pedantic reader. To my fellow pedants, I apologize.

Although I remain quite fond of Breath of the Wild and my memories of playing it, I cannot deny the fact that Elden Ring is (to me) a better game in almost every way. Crucially, it is not a game that would exist without Breath of the Wild, as it has clearly learned all of its most important lessons, but is also executing on those lessons better than Breath of the Wild ever did. I do not think that this perspective necessarily impacted my experience with Tears of the Kingdom, though it’s hard not to see Elden Ring as being the “truer” sequel to Breath of the Wild.

Early trailers for Tears of the Kingdom seemed to promise a Majora’s Mask-style follow-up, complete with a haunting tone and a surprising new style of gameplay (e.g., playing as Zelda..?). I would be lying if I said these violated expectations did not impact my perspective on the game.

Footnotes

His family lived in New Brunswick, to which they returned shortly after, and so there was no opportunity to return the magazine to the unfamiliar child in question. I do not know why he and his family was at my house. This issue of Nintendo Power was and remains the only issue of that magazine that I have ever owned.↩︎

It is perhaps unsurprising then that the game would be associated with a “real” curse, in the form of BEN DROWNED. It is beyond the purview of this discussion to explicate BEN DROWNED properly, but I will say that it is unquestionably my favourite creepy pasta, due in no small part to the fact that I watched it happen “live”, as I was lucky enough to be alerted to the story early and to be able to watch its events and updates play out in real time.↩︎

As a child, I would simply close my eyes and slam on the B button. I always dreaded the first time you put on one of the primary masks, as it would not allow you to skip the terrifying transformation cutscene on first viewing.↩︎

Perhaps someday I will write about how I think that Outer Wilds is a misfit hybrid of Majora’s Mask and The Witness, getting undeserved credit for (failing to do) what those two games had already done so well, but today is not that day.↩︎

Undoubtedly, it is not a flawless game and there are aspects of its gameplay that were simply better in Ocarina of Time (e.g., temple design). These comparisons are not within the purview of the present discussion and are, generally speaking, not of great interest to me.↩︎

It also helps that, in this case, the orange is deeply cursed.↩︎

I’m not sure exactly what Bioshock 2 was trying to do but I would prefer not to think about it for too long. I have not yet sipped on the contrarian draught of insisting that Actually Bioshock 2 Was Really Good and Maybe It’s Actually the Best in the Trilogy and I hope not to.↩︎

We’ll get to it.↩︎

How incredible is it that I can still go back to my Wii U and use its diary application to see when I played Breath of the Wild and for how long? And how depressing is it that that functionality is just not provided in the Switch at all (despite that data still being collected and sent to Nintendo)?↩︎

And depending on who you ask, perhaps one of only a handful of worthwhile open-world games.↩︎

It is actually fairly clear to me. It’s just more polite and narratively useful to pretend to equivocate.↩︎

The other notable addition to basic player mechanics, Ascend, allows players to rise through some ceilings. This is not a particularly interesting mechanic to me, although it is a useful tool for designing puzzles.↩︎

This is not necessarily because those elements of the game are unworthy of any discussion or should not be covered in a “proper” review of the game, but rather because of what they represent phenomenologically to the player: when I encounter these aspects of Tears of the Kingdom, identical as they are to that of Breath of the Wild, they generally do not elicit much reaction (or at least, the positive aspects do not). For better or ill, the experience of playing a sequel for many players is going to be defined by that which is novel.↩︎

My heart goes out to the players who did not unlock this mechanic early, either through luck or a congenital and pathological need to fully explore a videogame’s map as early in the game as possible. Literally burying this mechanic seems like an odd choice, to put it charitably.↩︎

Even this solution embitters me, as Breath of the Wild had a means for jumping high into the air built into the game in the form of Revali’s Gale. Replacing it with springs and Ascend is a clear downgrade.↩︎

If you are not a Newfoundlander, you may mentally replace the phrase “What odds” with the phrase “So it goes”.↩︎

For those who are interested in how, specifically, an open-world sequel to a traditionally-linear franchise can seamlessly integrate its gameplay and narrative, I would encourage you to seek out Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain.↩︎

I know for a fact that I am not the only player who simply walked away from the game, unpaused, allowing the rain to pass while you busied yourself not playing Breath of the Wild for a few minutes.↩︎

“Cheers” to fusing a rocket to a shield in order to get a one-time super jump, but “jeers” to having to fuse the same item to an arrow, repeatedly, one at a time, hundreds of times.↩︎

It has become increasingly common for cranks and contrarians to insist that the weapon durability system in these games is Extremely Good, Actually. As intimated in the primary text, one of their arguments in favour of the system is that it forces players to experiment with different weapons and styles of combat. As discussed, I do not feel that this the system is effective in accomplishing this goal. If one did wish to encourage this kind of player weapon heterogeneity, there are many different and interesting ways one could do so, including having a variety of enemy weaknesses to different weapon types (see: Fire Emblem, Pokemon, Dark Souls), or using the environment and context to encourage the use of different weapons and items (see: the entire Legend of Zelda franchise, with a special tip of the hat to A Link Between Worlds). A common counter-argument used against weapon durability nay-sayers is that “You’ll always have enough weapons! You never really run out!”, to which I reply: “Okay, so then why make me have any?” If the game is going to constantly spew its weapon garbage at me, then why not do away with the system altogether? If it’s not going to matter, then why make me engage in tedious item management? Why frustrate my experience of combat at all?↩︎

Admittedly, the Zelda storyline is the most interesting aspect of the game’s plot, although it too is not without considerable flaws. Because of the nonlinear structure of the plot, much of it is devoted to rehashing the exact same simple plot points, over and over. The end of every single Temple “reveals” the exact same plot point, a plot point that has already been revealed to the player (perhaps multiple times), should they have collected any of the flashback memories strewn throughout the map. The plot does contain precisely one extremely cool and touching moment, but it is tragically undone through Plot Magic at the conclusion of the game, utterly destroying any narrative stakes and betraying the trust of the audience.↩︎

In a beautiful little narrative flourish, this advice ends up being the solution to an optional puzzle presented at the very end of the game, used to unlock the game’s final mask.↩︎